Acknowledgment: This article benefited greatly from the insights and feedback of Lorcán Hall, Lorenzo Chan, Shelly Habecker, and Dirk Reinhard. Any remaining errors are the author’s own, and the views expressed do not necessarily reflect those of the reviewers or their organizations.

I recently returned from the International Conference on Inclusive Insurance (ICII 2025), an important global gathering of inclusive insurance experts and practitioners. For years, I had followed this event from afar, and this year had the opportunity to experience it firsthand. It was a week of optimism about innovation and progress, but also of unease about the questions the sector still struggles to answer. Across the industry, there is growing excitement about new models that expand the boundaries of what inclusive insurance can achieve — from Lumkani’s fire-detection and community protection network in South Africa, Pioneer’s integration of microinsurance into everyday financial services in the Philippines, and the World Food Programme’s Rural Resilience Initiative (R4). Together with many others, these initiatives capture the ingenuity and diversity shaping the future of inclusive insurance.

While many celebrate the progress reflected in the Global Findex 2025, there is growing recognition that this success rests on fragile foundations and a protection gap that remains largely unaddressed. Access to credit, savings, and digital payments has expanded dramatically in the last decade, connecting millions to the financial system. Yet when crisis strikes, most people and small businesses still lack the protection to withstand loss. We have made it easier to participate in finance, but not to financially protect what people build. This article explores that contradiction: how insurance, long the most neglected part of the inclusion agenda, remains its missing pillar.

This first piece in a series on resilience offers reflections, stemming not just from the words spoken on stage at the conference, but the questions exchanged in hallways and over coffee, where some of the most challenging issues were discussed.

We have made it easier to participate in finance, but not to financially protect what people build.

Recognizing the Insurance Protection Gap

The scale of the insurance protection gap is striking. Nearly 90 percent of people in low-income countries have no form of private insurance, and coverage across most emerging markets remains below 3 percent of GDP. This persistent gap is both a policy and market failure, and a deeper design flaw in how we define inclusion; measuring participation in the economy but not resilience to loss.

Slowly, this gap is starting to attract the attention it deserves. Across global policy circles, insurance is being recognized not as an afterthought but as a foundation for resilience and sustainable development. Discussions are underway to include insurance explicitly in the post-2030 UN Sustainable Development Goals. Institutions such as CGAP have sharpened their focus on insurance, now hosting the Access to Insurance Initiative (A2ii), and the World Bank’s Global Findex now includes, for the first time, an indicator on insurance coverage. Beyond policy interest, evidence is mounting that resilience, not growth, is the true measure of financial health. Data from CFI’s Small Firms, Big Impact research shows that micro and small enterprises place resilience above all else, valuing the ability to absorb shocks, protect livelihoods, and recover quickly when things go wrong.

How the industry addresses uncomfortable truths will impact momentum toward addressing the insurance protection gap. As industry veteran and Board Chair of the Microinsurance Network Lorenzo Chan put it, “The real milestone will be the day insurance is bought, not pushed.” The challenge runs deeper than marketing, reflecting how the sector builds value, fairness, and trust. If insurance is to become a product people want rather than accept, it must confront several realities that continue to hold it back: the overuse of trust as a convenient explanation for low demand, the dependence on predatory bundling to create uptake, and the unresolved question of who ultimately pays to protect the most vulnerable.

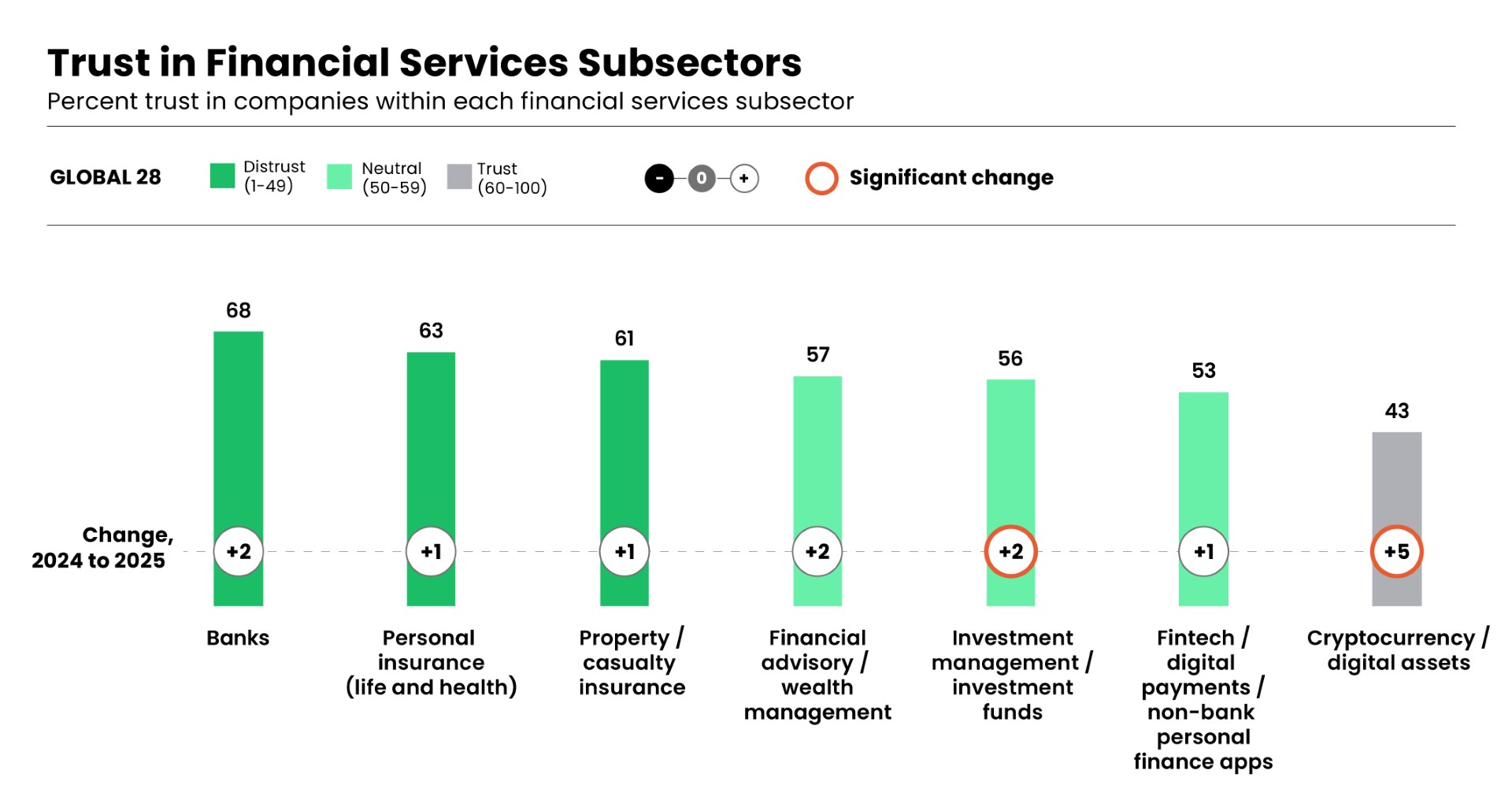

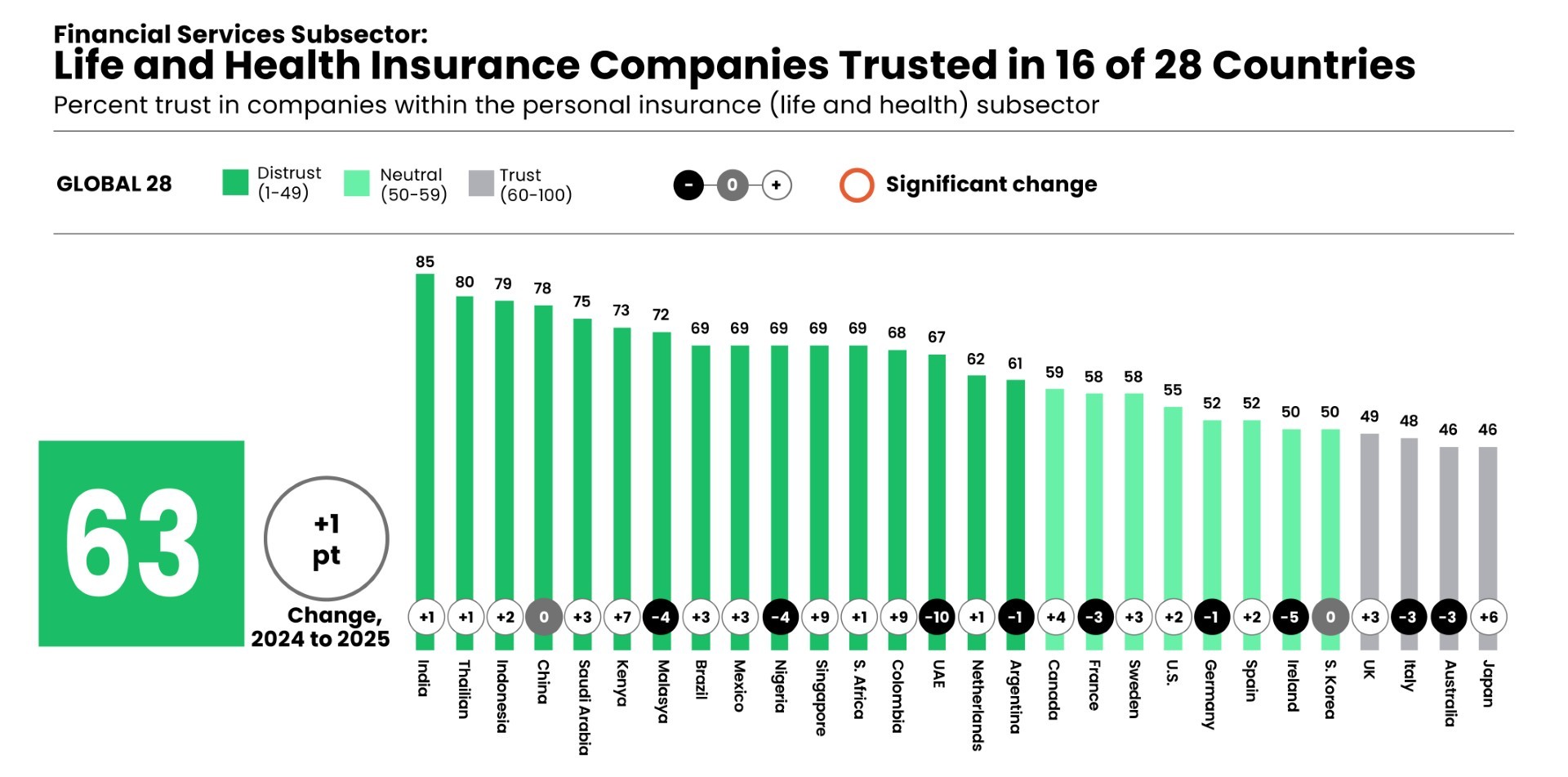

The default narrative in inclusive insurance is that low-income consumers don’t trust it. I’ve often fallen back on that framing myself, describing trust as the “currency of insurance,” one that is in short supply. And yet, evidence is increasingly complicating that story. The Edelman Trust Barometer shows that while insurance still faces skepticism, it ranks relatively high in consumer trust, especially in emerging markets. CFI’s research in Brazil and Indonesia revealed a large and largely overlooked segment we call the “persuadable middle”: microentrepreneurs who express both interest and intent when presented with insurance offerings. Many of them weigh insurance carefully, balancing hope and hesitation. They see its potential but have yet to encounter a product that feels trustworthy, affordable, and worth the commitment.

What if the trust problem doesn’t lie with consumers, but with the way insurers engage them? The term “trust” is often used as a catch-all to explain low uptake, but in practice it masks a more nuanced set of breakdowns: claims denied or delayed, product features that don’t match real-world needs, unintelligible exclusions, or a lack of empathy during customer interactions. These failings compound over time, embedding the impression that insurance cannot be relied on when it matters most.

Consider the claims experience: the moment of truth in any insurance relationship, when a promise must become action. At its core, what do people buy when they buy insurance? They are buying the insurer’s promise to pay a claim in times of need. In theory, they are also buying peace of mind, knowing that a financial safety net exists. When that moment goes wrong, it can erase trust that took years to build. Conversely, when claims go right and help families in need, they become the best advertisement for insurance. Lorenzo Chan’s mantra, “pay claims, pay claims, pay claims,” sums up this principle. For too many low-income customers, the claims process remains the weakest link, a test of endurance rather than support. Complex paperwork, inconsistent standards, and inflexible procedures turn what should be a moment of relief into a moment of frustration. The news of a denied claim travels faster than any marketing campaign ever will. The reputational damage from a single failed claim can ripple through entire communities, undoing years of outreach and investment.

There is also what seems like a paradoxical side to the trust gap. Many customers lose confidence and interest in insurance not because a claim was denied, but because they never needed to make one. Paying premiums year after year without a visible return can feel like wasted money, a perception that runs counter to the very logic of insurance. What appears to be frustration actually reveals something deeper: insurance promises peace of mind, not payout, and that promise can be difficult to value when money is tight and risks feel distant. Some insurers are trying to bridge this gap by creating value beyond the claim itself. In Nigeria, for example, Swiss Re and its partners developed a family health insurance model that rewards consistent premium payments and promotes preventive care, helping reframe insurance as something that benefits customers even when they are fortunate enough not to need a payout.

The real challenge is not persuading people to “trust” insurance, but ensuring the system proves itself when tested. The so-called “trust deficit” may, in truth, be a design and service deficit: the product of systems that still struggle to meet low-income customers with the urgency, fairness, and simplicity they deserve. To move forward, inclusive insurance must start confronting the habits within the industry that keep the trust gap alive.

Because genuine customer demand for insurance is weak, the industry has long relied on pushing policies onto people, sometimes aggressively, sometimes by stealth. One common approach is through compulsory or bundled insurance. If consumers won’t buy coverage willingly, the reasoning goes, then attach it to something they are buying. This is why we often see insurance bundled with other products: credit life insurance tacked onto loans, small insurance covers bundled with bank accounts or mobile airtime, or accident insurance included with a bus ticket. In the inclusive finance space, many micro-loans and savings accounts come with automatic insurance. The practice can be a pragmatic way to expand coverage, ensuring people are protected even if they never actively sought it out.

Yet, while traditional insurers often welcome compulsory schemes, the practice remains one of those thorny topics that make inclusive insurance veterans uneasy. Is it a necessary stepping stone toward an insurance culture, or a crutch that papers over the demand problem? The answer depends on how it’s done. If bundling is done transparently and the coverage provides real value, it can introduce people to insurance in a positive way. However, if it profits from customers’ ignorance, if people don’t even realize they have insurance, never file claims, and the insurer quietly pockets the premiums, it veers into exploitative territory. Unfortunately, there have been products, especially in mass microinsurance, where claims ratios are shockingly low — in the single digits. That means only a tiny fraction of the premium money paid ever goes back to clients as benefits; the rest is eaten up by high, and arguably excessive, distribution costs or profit.

Such unjustifiably low claims ratios undermine trust and hinder uptake. As one insurtech expert noted, if an insurance product pays out less than 30 percent of the premiums in claims, customers would be better off not having that insurance at all. The Landscape of Microinsurance 2024 estimates the global median claims ratio at 23 percent, with variation across regions and product maturity. For reference, in the United States, the Affordable Care Act requires health insurers to spend at least 80 percent of premiums on medical care in individual and small-group markets, and 85 percent in large-group plans. The contrast is stark, yet microinsurance operates in very different conditions, with smaller premiums, much higher distribution costs, higher per-policy operating costs, and more complex environments. That said, it is widely agreed that the claims ratio for microinsurance and inclusive insurance in developing countries must move toward the claims ratios for similar products in developed nations.

None of this is to say bundling or mandatory insurance should be abandoned. In fact, many of the most successful inclusive insurance schemes leverage partnerships with telecom companies, retailers, or microfinance institutions to reach scale. The key is customer awareness and value. If a micro-bundled insurance product is offered as part of a loan or airtime package, the client must know it’s there and must be helped to claim when eligible. This requires better communication and often simpler product design. If claims processes are over-complicated or payouts too small to bother with, clients will understandably ignore the product (or not even realize what they have). Making insurance easy to understand, easy to enroll in, affordable, and easy to claim against is a strategy to build trust and demonstrate relevance. Simpler, more transparent products tend to engender more trust (and cost less to administer), creating a virtuous cycle.

Compulsory or embedded insurance therefore can be a double-edged sword. It can drive inclusion at scale, but if done poorly with opaque terms, negligible payouts, and unclear redress mechanisms it reinforces the very apathy and distrust it sought to overcome. The inclusive insurance community increasingly recognizes that high volume, low customer value models are unsustainable. Products with extremely low claim ratios or that rely on customer unawareness are now being called out as extractive practices that do more harm than good for financial inclusion.

Another challenging conversation in insurance is about who foots the bill for covering the riskiest, most vulnerable segments. Premiums that are set purely by assessing risk and cost are often unaffordable to those who need insurance most, such as small farmers, climate-vulnerable communities, and the poorest households. This is where subsidies come in. In agricultural insurance, subsidies are effectively the norm worldwide. For example, in the United States’ huge crop insurance program, taxpayers cover roughly 63 percent of farmers’ premiums, while farmers pay only ~37 percent. In India, the government’s flagship crop insurance scheme caps farmer premium shares at just 1.5-2 percent of the insured crop value, essentially subsidizing the remaining 90+ percent of the cost. These massive subsidies recognize a reality that crop insurance would never achieve scale if poor farmers had to pay the full actuarial price (which can be prohibitively high, given frequent droughts, floods, and other perils). Public support is justified by the broader social benefits of protecting farmers’ livelihoods and promoting climate adaptation and food security.

Agriculture may be a distinctive case, but it highlights a broader point for inclusive insurance: reaching very risky or very poor customer segments often requires someone other than the end customer to bear part of the cost. This could be governments, donors, or cross-subsidies from other customer groups. Inclusive health insurance schemes, for instance, sometimes need premium subsidies or support for high-cost claims (like catastrophic illness) because the low-income users simply can’t pay enough to cover the risk. Similarly, disaster insurance for low-income homes might need public-private partnerships to work. There is a strong public policy rationale for investing in insurance as a social safety net — it improves access to healthcare, speeds up disaster recovery, and reduces poverty by preventing households from collapsing after shocks. Insurance coverage has positive externalities unaccounted for by pure market pricing.

However, subsidies in insurance raise tough questions. Who pays, and is it sustainable? If governments subsidize premiums indefinitely, is that the best use of limited public funds? Some argue that subsidies should be “smart” and targeted — for example, only for the poorest or for specific high-impact risks — and designed to eventually graduate customers into paying more as they become economically secure. Others note that subsidies can distort markets or lead to dependency if not handled carefully, and sometimes they fall prey to corporate capture, benefiting big insurers or larger farms more than those most in need. In some markets, the allocation of subsidies has even become a political tool, with local governments adjusting their extent or timing to gain favor during election periods. Reportedly, in India, where regulators require insurers to write a minimum volume of microinsurance, some companies choose to pay the penalty instead, highlighting how even well-intentioned mandates can fail when incentives are misaligned.

Finding the right balance between public support and market sustainability has become one of the defining challenges for inclusive insurance. In agriculture, the consensus is that some subsidy is necessary and worthwhile given the scale of covariate risks like drought. In other sectors, the debate is still evolving. Should health insurance receive government co-funding as part of universal health coverage efforts? Should climate disaster insurance for the poor be subsidized by climate funds or sovereign risk pools? These are difficult conversations, because purists would like insurance to stand on its own feet commercially, but reality may dictate a blended approach. The middle ground combines “smart” subsidies with other creative financing tools that can help extend coverage sustainability, such as capacity-building grants, concessional or first-loss capital to de-risk new portfolios, and results-based partnerships that reward scale or impact. For inclusive insurance to truly include the poorest and most vulnerable, the industry and policymakers will need to embrace creative financing solutions and new partnership models, while being honest about their trade-offs.

For inclusive insurance to truly include the poorest and most vulnerable, the industry and policymakers will need to embrace creative financing solutions and new partnership models, while being honest about their trade-offs.

What People Already Pay For

At the conference in Quito, Lorcán Hall, Senior Advisor to the SDG Academy at the UN SDSN, asked me to define the value of insurance, a (deceptively) simple question that has stayed with me. Because, in truth, people already pay for insurance, just not in the way we imagine. They pay for it after the shock: through savings wiped out by illness, assets sold to cover medical bills, or high-interest loans taken to rebuild after a flood or fire. They pay in lost progress, by cutting consumption, pulling children from school, resorting to harmful agricultural practices, and in livelihoods set back by years.

To understand the value of insurance, we need to see it not as an added cost but as a more efficient way of sharing and managing risk across society. Protection will always have a price; the real question is when and how we pay for it. Good insurance helps spread that cost before disaster strikes, turning private crises into manageable collective risks. Among those most vulnerable to climate shocks, for example, it can even help build resilience by reducing risk and incentivizing investment in adaptation. It is not charity, but infrastructure for stability.

Yet not every protection gap can or should be closed by insurance. Many risks, from climate shocks to economic disruptions, require broader systems of resilience: public safety nets, adaptable enterprises, and investments that prevent loss before it happens. That is where the next frontier lies. Beyond insurance, we need new forms of resilience capital, collective investments that make households, businesses, markets, and societies sturdier before the next shock inevitably comes.