In June 2024, a blistering heatwave sent temperatures soaring to 104°F across Bosnia and Herzegovina, triggering a massive power outage. Soon after, the demand for credit to purchase energy-efficient cooling solutions surged. This anecdote, shared by Senad Sinanovic, Director of Partner Mikrokreditna Organizacija, at the Annual MFC (Microfinance Centre) Conference, a gathering of microfinance institutions and practitioners from around the world, reflects broader global trends.

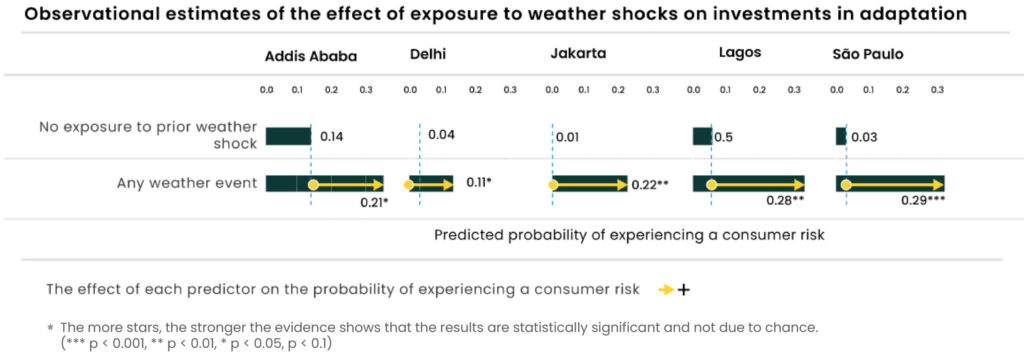

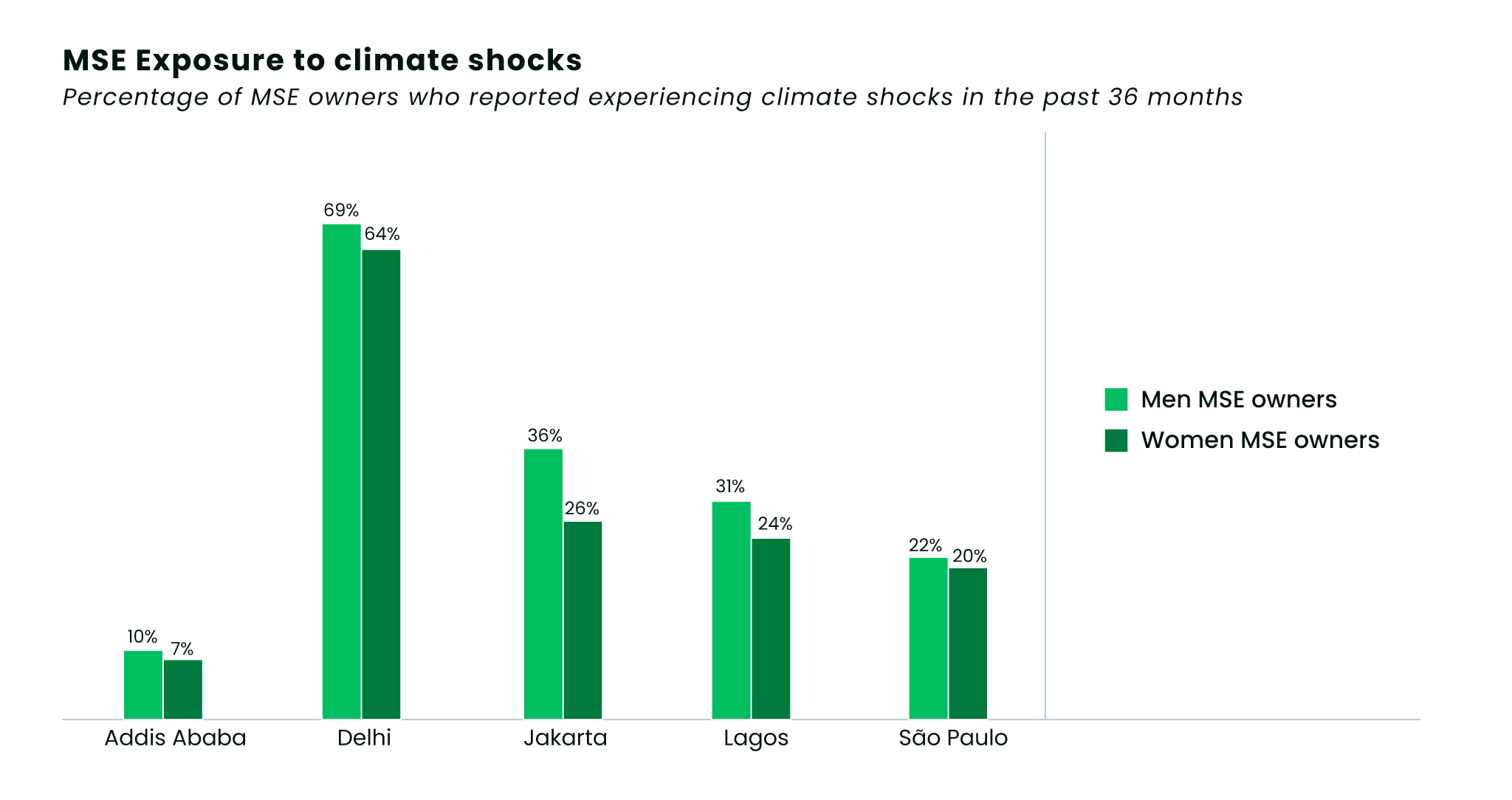

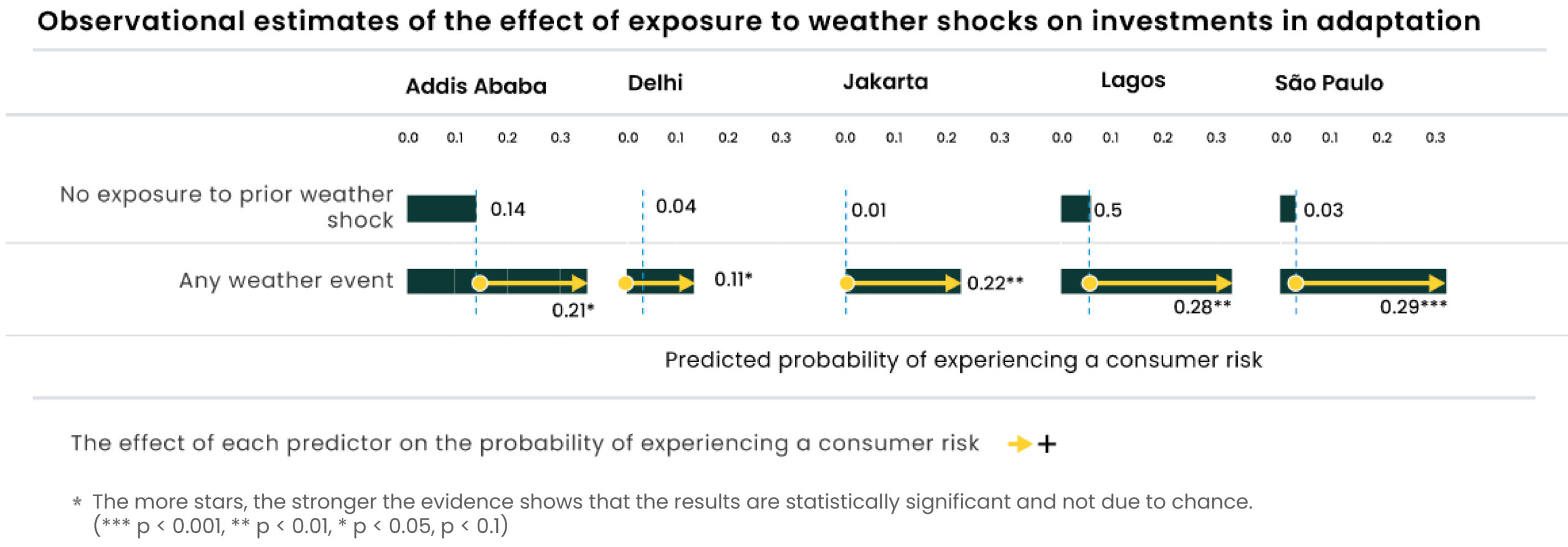

Recent research conducted by CFI, supported by the Mastercard Center for Inclusive Growth, shows that Micro and Small Enterprises (MSEs) are more likely to invest in climate adaptation after having experienced a climate shock. Studying over 4,000 MSEs across Addis Ababa, Jakarta, Lagos, Delhi, and São Paulo, our research noted that half of MSE owners in each of these markets experienced significant disruptions due to a range of climate shocks, motivating many to search for and adopt a diversity of short- and long-term coping strategies. Exposure to a climate shock motivates many MSEs to seek adaptation solutions. This trend was evidenced across all markets, even after accounting for the MSE owners’ education level and business experience, with the effects being most pronounced in Lagos and São Paulo.

Across all five cities, climate shocks are becoming a regular part of doing business. Half of all MSE owners surveyed said they experienced significant disruptions in sales and operations due to extreme weather events, including heat and heavy rain.

“During summer, I rarely get customers. However, I have to keep the shop open. We face difficulties in obtaining goods from the wholesale market, and sometimes fall ill because of the heat…and when it rains, water enters the shop and damages clothes.” – Apparel retailer in Delhi

In Delhi, over 65% of MSE owners — the highest in the sample — faced a climate-related shock in the past three years, including heatwaves, erratic monsoons, and severe winters. Over a quarter of MSE owners in Jakarta and Lagos reported exposure to climate shocks. Jakarta-based MSEs faced heatwaves and flooding, while Lagos entrepreneurs primarily dealt with torrential rain that triggered accidents, waterlogging, and power outages. MSE owners in São Paulo struggled with delayed payments and the cascading effects of disrupted supply chains, while Addis-based businesses faced infrastructure failures, particularly power outages during periods of heavy rainfall.

Over 50% of businesses in each city reported a decline in sales and profits due to climate-related shocks, with the impact being most pronounced in Addis Ababa and Jakarta. Yet, MSEs in Delhi appear to have faced fewer losses and disruptions. Furthermore, 35% of MSE owners from Delhi reported an improvement in production and sales, which could be attributed to the nature of the business or the entrepreneurs’ level of preparedness and ability to identify and seize new opportunities.

Qualitative and quantitative research suggests that depending on the intensity of the climate shock on the business, the recovery time varied considerably. Over forty percent of entrepreneurs from Jakarta reported not making a full recovery even three years after the shock. On the other hand, nearly 45% of MSEs in Addis Ababa, Jakarta, and São Paulo had recovered from the shock. In comparison, 50% of small businesses in Delhi and nearly 30% or more in other markets were in a better position than before, indicating the inherent resilience of small business owners in emerging markets.

Similar to Partner’s experience in Bosnia, CFI’s research found that MSEs who had experienced climate shocks were more likely to proactively invest in adaptation measures. MSEs employed a range of coping mechanisms. They ranged from short-term fixes — relocating business premises, adjusting business hours, or offering home delivery — to long-term investments in infrastructure and operational strategy. Some shifted from wholesale to retail; others leveraged digital platforms to expand their reach. In Jakarta, one entrepreneur selling mobile phones and accessories joined GrabMart in the aftermath of recurring floods and significantly boosted sales.

“I started to offer home visits to customers during heavy rains. While this is more convenient for many of our clients, it is too time-consuming to visit each client. It was a quick fix for a specific situation.” – MSE owner in São Paulo

Community-level solutions also emerged as a common coping mechanism, underscoring how MSEs innovate under pressure. A group of fishmongers in Delhi reduced their inventory and pooled resources to procure shared storage solutions in the summer. Similarly, in Addis Ababa, MSEs planted trees, organized cleanup drives, invested in improving the drainage and sanitation infrastructure, and rented tankers to pump out floodwater, working together to recover and better prepare for future climate events.

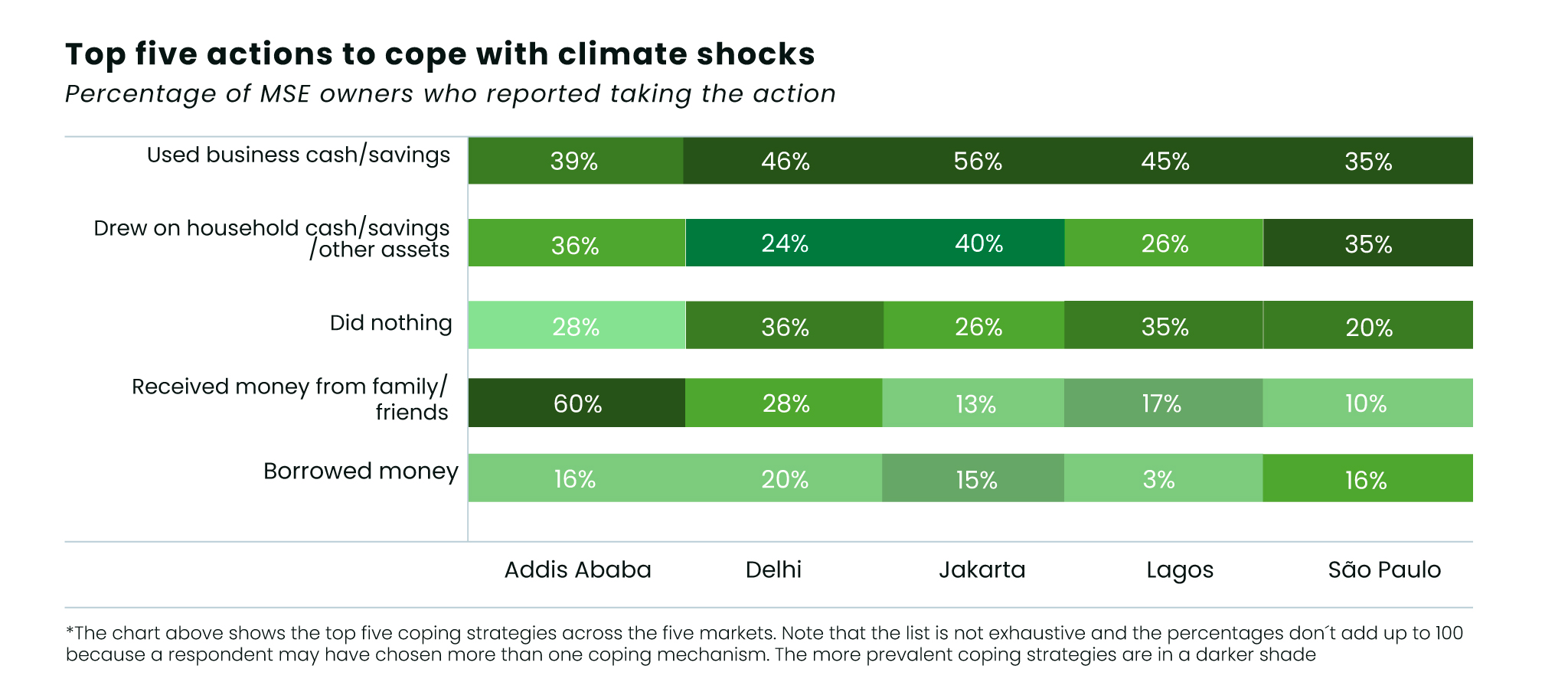

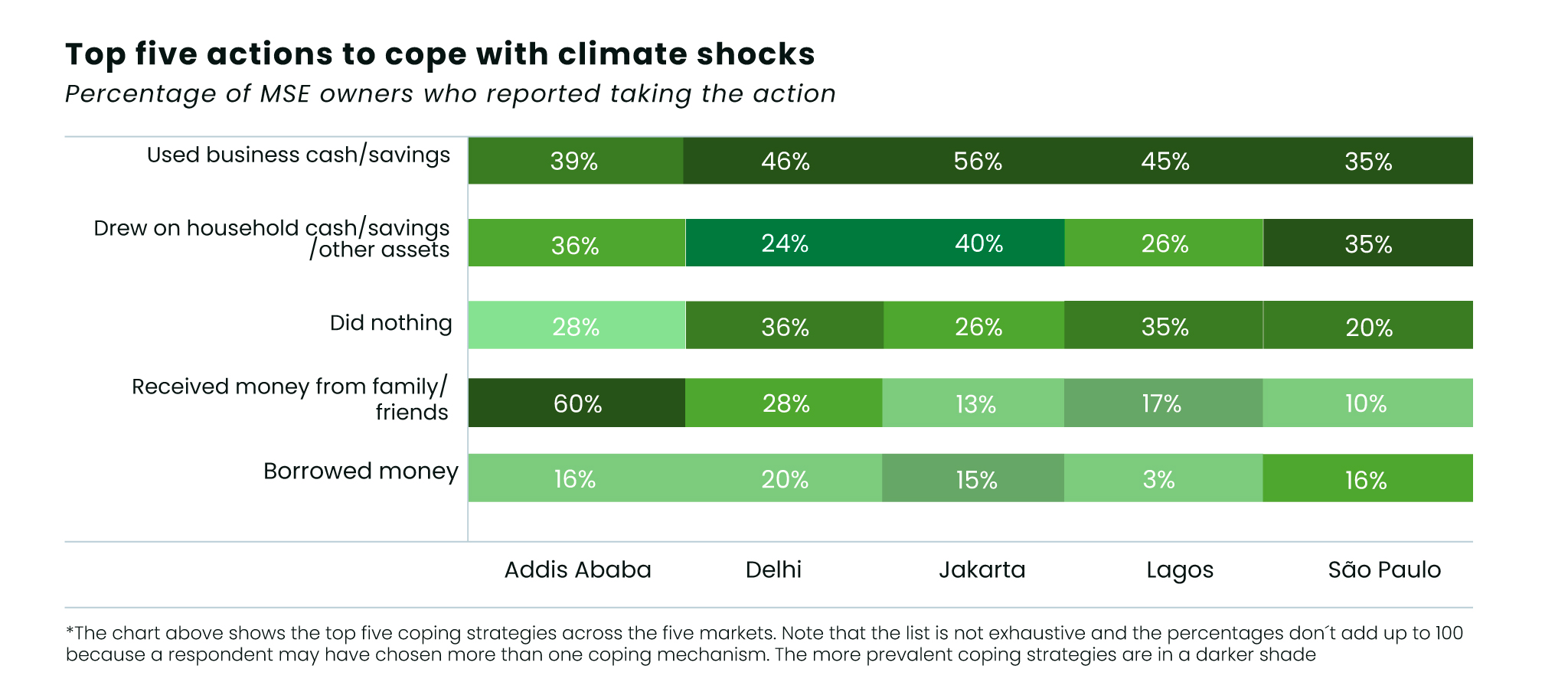

As climate shocks become more prevalent, MSEs often find themselves leaning on informal financial support. Savings and social networks serve as crucial financial lifelines during times of crisis, and in many cases, the line between business and home finances remains blurry.

Many MSE owners reported that, to the extent possible, they kept some money aside for business emergencies and used it in the event of economic and climate shocks. Tapping into household savings to meet business needs was also a common coping mechanism, highlighting the limited separation of finances between the household and the business in the case of small, informal enterprises. Leveraging business and household savings sufficed when the expenses were small. However, when the losses were more substantial, MSEs often turned to their social networks for financial support and business referrals. In Addis Ababa, informal savings groups commonly serve to meet cash requirements, in addition to being a source of community support.

“I borrow from friends and family members. For me, going to the bank is a curse. They require guarantors and an overwhelming amount of paperwork, which can be confusing and overwhelming. If the loan is not paid on time, the interest rate doubles. It causes a lot of anxiety.” – MSE owner in Addis Ababa

While some entrepreneurs reported having credit lines with banks or borrowing from microfinance, loans were often the last resort. Insurance, too, remained under-leveraged. Fewer than 2% of businesses rely on insurance. Some MSE owners mentioned purchasing insurance to include natural disasters or transit insurance to protect goods from weather-related damage, but the majority felt that it was either irrelevant or unaffordable. In Jakarta, one entrepreneur expressed skepticism regarding the likelihood of getting claims settled promptly. In São Paulo, another explained that Brazilians, in general, were not familiar with the concept of insurance as a risk management strategy. Others were unsure about how insurance could protect something as intangible as climate risk, pointing to an opportunity to build awareness around weather-indexed and other insurance products, coupled with providing positive customer experiences.

“I don’t think people care about insurance for climate-related issues. In Brazil, there is no culture of insurance. For example, less than 1/3 of vehicle owners in São Paulo have insurance. Crashing a car or having it stolen is significantly riskier than a flood or lightning striking your business. Here, we rely heavily on credit. If the car is stolen, finance another one, and you are good.” – MSE owner in São Paulo

Our research shows that adaptation investments tend to happen after a shock — when the need is urgent, but resources are limited. When investments are made as a reaction to climate shocks, entrepreneurs may not have sufficient time to negotiate pricing and access suitable financial services, which in turn limits their ability to adopt the most effective adaptation strategies. As seen in the study, most adaptation investments were self-financed and often required entrepreneurs to draw on their personal finances, which were often insufficient to make lasting, structural changes or invest in new equipment. For example, several MSE owners in Delhi stated that while they wanted to purchase sustainable cooling products, such as environment-friendly air conditioners, these products were rarely affordable. MSEs, particularly those in Addis Ababa, recognized that relying on personal savings and informal sources of finance was seldom sufficient for making longer-term investments, such as securing flood-resistant business premises.

To change this pattern, financial services and products must be designed to anticipate these moments and provide support before the damage happens. While MSE owners concurred that the government should be responsible for making infrastructural investments and supporting small businesses, access to well-designed financial services can also help MSEs make some of these much-needed structural investments and adapt to climate change. Studies show that the spike in demand for insurance products immediately after a climate shock is often temporary and tends to reduce as the losses fade from memory, offering a potential window of opportunity for providers to better understand the motivations and priorities of customers.

According to the World Bank, climate change and natural disasters are expected to push an additional 132 million people into poverty by 2030. Our research reveals that, while most MSE owners seek stability, given the increasing frequency and intensity of climate shocks, entrepreneurs across all markets are struggling to invest in durable adaptation solutions, which often limits their ability to recover fully. Despite needing financial services, MSE owners shied away from formal financial services for myriad reasons, including high costs and complex documentation requirements, limited understanding of how insurance could protect against climate shocks, and low trust in financial service providers (FSPs).

We hope that financial services and insurance providers can leverage this research to better understand when low-income clients who are MSE owners are more likely to invest in climate change adaptation. To better support MSEs in adapting to and building resilience against climate change, we propose the following takeaways for financial service providers (FSPs), fintechs, and insurers to consider.

- Design adaptation-focused credit products: Well-designed credit can help MSEs strengthen resilience, plan for and invest in effective adaptation solutions without depleting their savings. In some cases, FSPs are offering locally led, innovative solutions that are affordable and help consumers and small businesses adapt to climate change without causing environmental harm. For example, the Indian NGO Mahila Housing Trust has been offering its members small loans of up to US$75 to purchase heat-reflecting white paint and roof panels that can reduce heat absorption in their homes. Evidence from Bangladesh shows that emergency loans provided to farmers helped them adapt to flood risks, while being profitable for the MFI. Similarly, Atram, a Kenyan fintech, is leveraging AI-driven forecasting systems to provide early warnings of climate shocks a week in advance to MSEs, along with a customized plan and pre-approved emergency credit. While these are still early days and more evidence is needed to understand the impact of these solutions, innovations combining credit provision with providing timely information can help MSEs protect their businesses from climate shocks and minimize losses.

- Position insurance as a tool for building climate resilience: Insurance is a powerful risk transfer mechanism that can enable MSEs to build resilience against climate shocks. Parametric insurance, which offers fast and flexible payouts based on predefined triggers, can help communities recover from extreme weather events and strengthen resilience, as evidenced in India and the Philippines. While typically used to protect against natural disasters, recent parametric insurance models are providing coverage for pure economic losses not caused by damage to physical assets, which could support MSEs to recoup losses from reduced sales or event cancellations due to climate shocks. Additionally, anticipatory insurance products that forecast disasters and provide payouts in advance of humanitarian and natural disasters could also be piloted with MSE segments. Insurance adoption also involves cultural nuances, highlighting an opportunity for insurers to understand the local context, strengthen customer awareness, foster positive and reliable onboarding and claims experiences, and incentivizing customers to proactively adopt resilience-building measures, thereby building trust and demonstrating the potential of insurance in enhancing the adaptive capacity of MSEs in emerging markets.

- Enable MSEs to embrace digitization: Our research noted that the adoption of digital solutions boosted business growth and enhanced MSE owners’ ability to secure emergency funds and strengthen resilience. MSEs relying on digital platforms, social media, and digital payments to sustain businesses, communicate with customers, and conduct transactions and access funds when extreme weather events made it impossible for them to open stores or venture outside, reported positive business outcomes. Yet, context can impact digitization. Over 35% of MSE owners in Jakarta and 50% in Addis Ababa did not use any digital solutions. While the lack of basic infrastructure prevented many MSEs in Addis Ababa from adopting digital tools, MSEs in Lagos and Jakarta were deterred by the high cost of switching to digital solutions. On the other hand, MSEs in São Paulo and Jakarta were concerned about platform reliability, data privacy, and security. These barriers highlight opportunities for FSPs to address structural issues and design affordable, user-friendly digital solutions that help MSEs establish a digital presence, access a range of financial services, and improve efficiencies while safeguarding them from harm. Doing so will not only enable MSEs to reap the benefits of the digital economy but also help FSPs tap into a segment with huge scale potential and unmet needs.

Climate shocks are becoming a recurring experience for MSEs across markets. Entrepreneurs are innovating and adapting, but they frequently lack essential tools and resources to build stability and long-term resilience. FSPs, fintechs, and insurers must act urgently to develop solutions and lasting systems that empower MSEs to anticipate, adapt, and thrive in the face of climate disruptions.

Furthermore, given the critical role consumer protection plays in creating a safe space for MSEs—many of whom are new to the digital ecosystems — policymakers and regulators must work with FSPs to develop measures that safeguard MSEs from harm and ensure financial services are delivered responsibly. Doing so will create a resilient ecosystem where small businesses can utilize financial services and prosper, while supporting overall financial sector stability.

Introduction

The impact of climate shocks on MSEs

How MSEs adapt to climate shocks