Over the past five years, as evidence has mounted that financial access and usage are not the panaceas for the well-being of low-income people, there have been increased calls to answer the question “financial inclusion for what?”

The term financial inclusion presents a binary end state – people are either in the financial system or out of the financial system. This makes sense in nascent markets where few people are integrated into the financial system, but it increasingly has little value when the issue is not about access but about the quality of that access. Through measurement frameworks like Findex, the term financial inclusion has become synonymous with having access to a transaction account. In most developed markets and even in emerging economies like Kenya and India, inclusion is no longer the bottleneck. Increasingly in both developed and developing markets, the financial system is failing to create value for the majority of people. While there is some evidence that a transaction account can be helpful (especially in receiving remittances), it’s obvious to most people that an account will not be transformational.

The drumbeat around financial health has been growing, and increasingly stakeholders are doing a ‘search and replace’ for financial inclusion with financial health.

At the same time, the drumbeat around financial health has been growing, and increasingly stakeholders are doing a ‘search and replace’ for financial inclusion with financial health. But is this shift warranted? Part of the reason that ‘search and replace’ is convenient is that nothing else has emerged as a clear north star for inclusive finance, and thus the vacuum creates an opportunity for simple answers. The more cynical reason is that this is yet another donor-driven cosmetic shift about something that feels good but does not represent meaningful change. In other words, it’s another false narrative like the many we’ve had before in inclusive finance.

Financial health has been defined by a working group convened by UNSGSA as “… the extent to which a person or family can smoothly manage their current financial obligations and have confidence in their financial future.” It’s most easily understood by the measurement frameworks used to capture it, which are discussed in UNSGSA’s introductory paper for policymakers. It includes the following components:

- Managing the day to day: smooth, short-term finances to meet financial obligations and consumption needs

- Resilience: having the capacity to absorb and recover from financial shocks

- Goals: being on track to reach future goals

- Confidence: feeling secure and in control of finances

Interestingly, the drumbeat around financial health is garnering less attention from those who prioritize the evidence and those who learned a thing or two from prior false narratives we’ve experienced in inclusive finance. I see four reasons why the financial health concept is not the north star for inclusive finance and one area where financial health measurement may be useful.

1. The theory of change is flawed

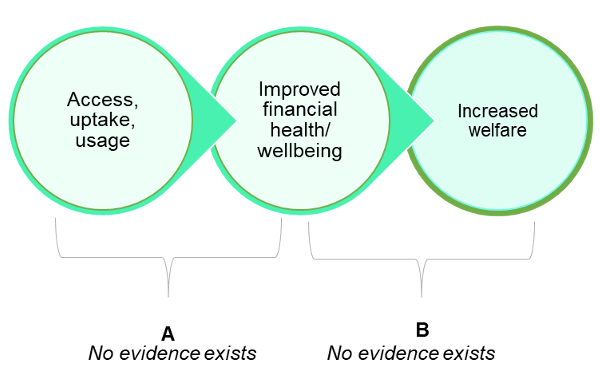

Financial health is considered an intermediary step that builds on a customer’s access to finance and supports their ability to effectively utilize financial services to improve their lives (see Figure 1). For this conceptual framework to hold, there is a need for rigorous evidence demonstrating that increased access, uptake, and usage of financial products and services leads to improved financial health (A in Figure 1), which, in turn, catalyzes greater welfare (B in Figure 1). However, research shows that despite near-universal levels of inclusion in the United States, only a third of Americans were financially healthy, while in Kenya, where there have been dramatic increases in inclusion, financial health levels have continued to deteriorate. In other words, the data shows an inverse relationship between increased access and usage with financial health.

While there is no research linking the broader concept of financial health to welfare improvements, there is an abundance of evidence, the most notable of which is a paper by Suri and Jack, that points to one component of financial health – resilience, or the ability to withstand a shock – as having direct benefits to overall welfare, including poverty reduction. Thus, one can achieve welfare benefits without achieving success in all four components of financial health.

Evidence supporting the broad concept of financial health to improve welfare outcomes – such as the ability to access opportunities in education or make long-term business investments – is also lacking. This suggests a clear disconnect in the conceptual framework underlying financial health.

Figure 1: Theory of change linking access to financial health and beyond

2. There is no universal standard or definition – or measurement

While the Financial Health Network (FHN) in the United States has established a measurement framework for the U.S. that takes into account contextual factors, efforts to globalize measurement have fallen short. In 2017, CFI partnered with FHN to adapt the concept for emerging markets and tested the concept in Kenya and India. It found that the contextual factors were significant and were major drivers of people’s outcomes but did not propose a method to correct these important drivers. Others have gone on to test different frameworks. Gallup narrowed the concept to financial security in order to achieve cross-country comparability, and IPA has narrowed it even further to “having access to resources in an emergency,” aligning well with the evidence noted above that the link between resilience and well-being is clear. UNCDF has found an elegant solution to this divergence in the evidence, noting that the drivers of financial health and the measurement of financial health are two separate things.

3. It’s another distraction from what really matters

Financial health measurement doesn’t help us with the full story around the drivers of people’s economic vulnerability. Imagine these scenarios:

- An unemployed factory worker in Eastern Europe gets unemployment benefits when she loses her job. She is able to pay her rent and utility bills and may even be able to save some money left over from the unemployment benefits. She is planning for the future and is thinking about starting a business.

- A college student in India relies on his parents to pay his tuition and housing while he’s studying in Bangalore. Repeatedly, the student is using his tuition money from his parents to go on holiday with friends or to buy the latest tech gear. He’s consistently in arrears on his tuition, rent, and utility bills. He doesn’t think about next semester or what his parents will do. He likes to live in the moment and is confident that through his family connections, he’ll find a high-remunerative job when he graduates.

- A villager in Malawi receives monthly remittances from her son in the capital. She receives no government assistance, and without this money, she would have no other means to buy food and pay for electricity. But she is certain her son will always come through, so she has confidence in her future.

Which of these people are financially healthy? Is paying their bills on time a sufficient measure? Does knowing their attitude toward the future tell us something about the risks they are exposed to? And what should policymakers do with this information?

I’ve heard people claim that poverty measurement is inadequate and that we need financial health measurement as a more accurate depiction of people’s well–being. In the scenarios above, I believe poverty measurement would give us the information to figure out that the villager in Malawi is the most vulnerable of the three, whereas financial health measurement would signal to us that the college student in India is where our attention should be placed. For these reasons, financial health can act as a distraction from what matters.

4. We know better already

The field of inclusive finance has already lived through the false claims around poverty eradication. We learned from this and spent a decade documenting the evidence and more seriously considering our language when making claims. We’ve now made significant strides in improving the evidence base that shows that inclusive finance has significant and meaningful benefits at the individual, household, and community levels. CGAP’s updated theory of change lays out a realistic — and by no means simplistic — pathway toward how financial services could lead to positive outcomes around resilience and opportunities for low-income people. That path is built around the evidence and shows that positive outcomes can be achieved through many channels, like government safety nets in the Eastern European scenario. Why dare I ask, would we want to go back to looking for simplistic answers to complex challenges?

And the benefit is….

There are clear benefits to financial health measurement. While it should not be the north star for where we as an industry are going, it can be a great indicator of the financial system at large. UNSGSA’s advocacy agenda on financial health notes one important benefit of financial health measurement: it provides us with a pulse check on what’s happening in a market. In other words, financial health measurement can be a barometer of the broader financial system. Financial supervisors can use this to measure the temperature of how the financial system is doing. Existing demand-side surveys – whether that’s Findex, FinScope, or other research funded by providers or the government – could pull out key variables and aggregate them into an index on financial health. This would give a pulse not so much on the behaviors or choices of individuals, but a temperature check on the institutions in the financial system. In the U.S., for example, where the majority of Americans are not financially healthy, the financial health pulse would signal to the Federal Reserve that more oversight is needed. It might also nudge politicians to look at the biggest drivers of financial vulnerability, namely excessive health costs, and look at reforming the health sector.

While it should not be the north star for where we as an industry are going, financial health measurement can be a great indicator of the financial system at large.

Using financial health as a pulse on the financial system and broader policy agenda would be beneficial. But are policymakers and financial supervisors ready to use it in that way and not just come out with statements about how Americans are unable to save $400 for an emergency? Unfortunately, a quick look at the headlines shows that financial health measurement is not yet leading to the policy outcomes it was intended to solve and is mostly used to point to behavior changes that poor people need to make, like drinking fewer cappuccinos.

A simplistic narrative for a complex problem doesn’t seem to work. Perhaps if we devoted our attention to understanding and measuring the drivers of vulnerability, we might have more to say about the appropriate financial policies that are needed.