The impacts of COVID-19 on small and medium-sized businesses in Nigeria, Colombia, India, and Indonesia are changing all the time. But one thing has remained constant since March 2020: low-income people in emerging markets are still dealing with extreme challenges and major disruptions to their livelihoods. While business closures have declined since their pandemic peak and MSMEs are employing more people, recovery in areas such as household resilience and coping strategies has not brought things back to pre-pandemic levels and has not kept pace with recovery in developed markets.

Below is the first in a series of blog posts zeroing in on key takeaways from our ongoing, longitudinal research in these markets.

The first four waves of data from Lagos are analyzed in this post. Data visualizations from Wave 5 results from Lagos will be posted here later in August 2021; Wave 6 will follow shortly thereafter.

In the coming weeks, the second and third posts in this series will feature COVID’s impacts in Indonesia and India, respectively.

This research is part of our partnership with the Mastercard Center for Inclusive Growth. See also the accompanying slides for additional charts and insights.

1. Nigeria’s economy was fragile before the pandemic began.

According to the World Bank, Nigeria’s economy had not fully recovered from the 2014-16 economic recession, which was driven by a decline in oil prices, by the time the pandemic struck. In fact, before the pandemic, the World Bank and IMF downgraded its economic growth forecasts from a projected 2.5 to 2 percent.

2. Restrictions on movement and simultaneous declines in oil prices lead to a reduction in aggregate demand and an economic contraction.

In response to the pandemic, Nigerian officials instituted widespread restrictions on movement throughout the country. This depressed aggregate demand by closing shops and preventing people’s movement, exacerbating the economy’s weaknesses. Data from the MAP surveys highlights this: nine percent of all businesses closed, and of those, government restrictions were the primary cause of closure for 55 percent of businesses. Additionally, the data indicated a significant drop-off in customer traffic to shops, and 80 percent of firms reported declines in profit levels in the immediate aftermath of the pandemic. Simultaneously, global oil prices crashed from a high of $59/barrel in February to a low of about $19/barrel by April, reducing government revenues at a time when fiscal resources were needed for a response. Oil prices have since recovered to above pre-pandemic levels to around $69.

3. The impact of this contraction on MSME owners was dramatic, making it difficult for owners to cover expenses and leading to significant layoffs.

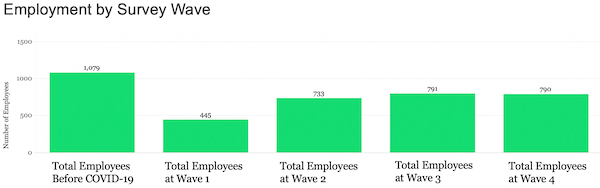

The decline in profits mentioned above foreshadowed widespread inability by owners to cover their expenses from revenues alone: 45 percent of owners said they could not do this in the months following the start of the pandemic. Widespread layoffs were followed by a 55 percent reduction in the workforce by July of 2020. Impacts of similar types and magnitude were seen in surveys by BFA, i2i, and the World Bank.

4. Households suffered as incomes declined — they were unable to cover expenses for household essentials and experienced dramatic food insecurity.

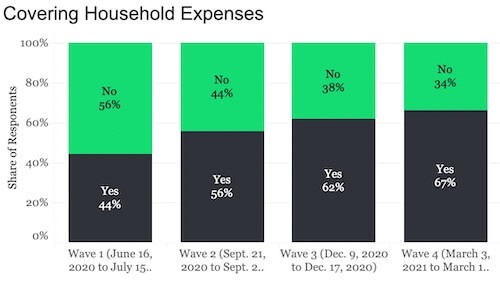

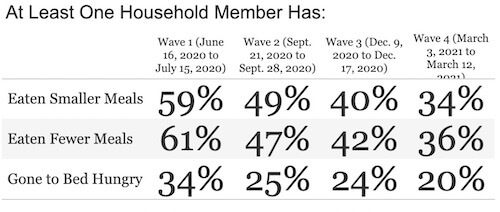

The MAP surveys showed that owners’ households experienced declining fortunes along with their businesses. The share of business owners reporting they could not cover household expenses was 56 percent. Responses on food insecurity reflected this vulnerable financial position: 60 percent of owners reported they or someone in their household had eaten fewer or smaller meals since the pandemic began because there was not enough money to buy food; 34 percent of owners reported that they or someone in their house had gone to bed hungry in July 2020. These responses were emblematic of the pervasive challenges facing other Nigerians, with studies showing widespread food insecurity across the country.

5. Owners’ businesses and households partially rebounded as government restrictions eased.

Nigeria began easing restrictions in movement in July 2020, and data from the second wave showed that businesses partially rebounded. For instance, the MAP surveys showed that half of the owners with a closed business in Wave 1 had restarted operations or started a new venture in Wave 2. During the same period, the number of employees at MSMEs increased by 70 percent, and the share of businesses reporting they could cover their operating expenses increased from 54 to 60 percent. Marginal improvements in household resilience accompanied those advances, with the share of owners reporting their households could cover their essential expenses increasing from 44 to 56 percent, and the share of owners reporting the worst food insecurity declined by 8 percentage points.

6. However, these initial gains appear to be tapering off, raising the specter of persistently lower economic performance.

Gains in the number of operating businesses between Wave 1 and Wave 2 were substantial. Increases in the percentage of businesses that were operating were smaller but steadily increased between waves 2 and 4. Wave 4 survey data from March 2021 shows that 1.75 percent of businesses were closed in compared to 4.25 percent in Wave 2. However, the share of owners reporting they could cover business expenses from revenue increased by only one percentage point between Waves 2 and 4; and employment levels remained largely unchanged (resting about 30 percent below their pre-pandemic peak). While the share of owners reporting their households could cover essential expenses improved from 56 to 67 percent, food insecurity declined only somewhat between Waves 2 and 4 (even in Wave 4, 20 percent reported at least one member of their household going hungry).

7. Business owners’ financial tools have been stressed by the pandemic, hampering their ability to bootstrap recovery.

In the year before the pandemic, an equal share of owners reported having made a savings deposit and a savings withdrawal. Between the start of the pandemic and the Wave 1 survey, the share of respondents reporting they made a withdrawal was more than double the share reporting they made a deposit (28 percent saved versus 64 percent withdrew savings), indicating a major drawdown of cash reserves. This pattern moderated in Waves 2 and 3, but only slightly. Data from the later waves also confirmed the extent of the spend-down with respondents reporting they had used around 60 percent of their savings by Wave 4. Borrowing has appeared to be the primary financial tool to fill this gap: the share of respondents reporting receiving a new, formal loan increased from 14 percent in Wave 1 to 41 percent in Wave 3. However, a large share (56 percent in Wave 1, 45 percent in Wave 2, 39 percent in Wave 3, and 31 percent in Wave 4) of respondents reported that they have skipped a loan payment as a coping strategy.

8. They also appear to have few lifelines available to help relieve stress on their finances.

The MAP surveys also show strong evidence that business owners have few mechanisms to ease pressure on their finances. As noted above, while borrowing has increased, there is evidence that the ability to repay is a challenge. About one-third of respondents have taken loans from friends and family — which tend to be shorter-term, cheaper, and more flexible than formal loans — since the pandemic began. Other support from friends and family is limited. For instance, MSME owners are much more likely to be the sender of domestic cash transfers to friends and family than recipients and only a small share of owners reported receiving international remittances. Government support has also been paltry, with only 5 percent of MSME owners reported receiving a government transfer of any kind since the pandemic began.

9. Consequently, owners appear to be relying on sweat equity, price adjustments, and payment arrangements to boost revenue.

With financial stress ongoing, owners have turned en masse to improving their fortunes by contributing sweat equity. With government restrictions lifted, a growing share of respondents (about 50 percent in Wave 1 and 64 percent in Wave 4) reported working longer hours to make ends meet and satisfy customer demand. Meanwhile, increasing shares of respondents are adjusting their prices — slashing prices on some goods, putting a premium on others — to move inventory, and respondents have grown increasingly likely to experiment with offering store credit or not. Not all these strategies are complementary, and there is some evidence that the use of a mismatched set of coping strategies is not helping businesses.

10. It remains to be seen if international aid agreements will fill the fiscal stimulus gap, accelerate growth, and aid MSMEs’ recovery.

Nigeria’s cash-strapped government has been able to offer limited fiscal stimulus to boost aggregate demand so far, hampering a recovery. The stimulus that has been offered has been relatively small, offered in the form of targeted credit facilities, and aimed at small and medium formal firms in specific, hard-hit sectors like aviation, hospitality, and manufacturing — none of which is likely to benefit MSMEs like those in the MAP survey. At the end of 2020, the World Bank announced a $3 billion agreement to support Nigeria’s recovery, including $750 million for the Nigeria COVID-19 Action Recovery and Economic Stimulus (CARES) program, which aims to get aid to provide social transfers to low-income households, improve food security, and support MSMEs. Future waves should hopefully show if this aid improves MSMEs owners’ financial well-being.

Keep following this space for more key survey insights from microfinance clients in Lagos as well as India and Indonesia.