Topics

Series

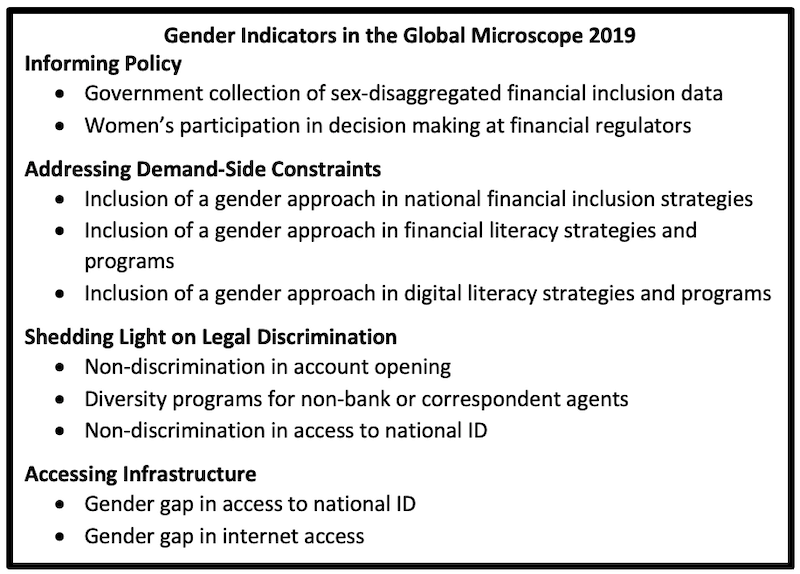

The Economist Intelligence Unit’s (EIU) Global Microscope 2019 was updated with 11 indicators that shed light on a country’s likelihood to create a more enabling environment for women’s financial inclusion. While the Microscope doesn’t rank the countries on these indicators, the premise is that countries with gender-oriented policies or infrastructure in place are more likely to be enabling for women’s financial inclusion. These indicators can be subcategorized into four buckets: policy, constraints, discrimination, and infrastructure:

Country-level data reveals that the index doesn’t actually help us get closer to understanding which policies drive financial inclusion for women, however.

Let’s use the Philippines and Bangladesh as examples. Both countries have three of the Microscope indicators in place. Yet the Philippines is one of the few countries in the world where women’s access to financial services exceeds that of men (39 percent for women versus 30 percent for men, according to the Global Findex 2017). On the other hand, Bangladesh has one of the largest gender gaps in access in the world at over 28 percent (64 percent for men versus 36 percent for women). The fact that such different outcomes are measured equally using Microscope’s index signals that women’s financial inclusion requires much more than what is captured by these indicators.

The reality is that what may appear to be a barrier in one country for women’s financial inclusion may not be a barrier in another. Let’s look at one of the indicators: diversity programs for non-banking or correspondent agents. This indicator is highly relevant for countries where norms may limit women’s ability to engage with male agents but this issue wouldn’t be a direct barrier in cultures where women have freedom to move and engage with whomever they choose. Thus, its existence or lack thereof may or may not have an affect on women’s financial inclusion in that particular country.

What may appear to be a barrier in one country for women’s financial inclusion may not be a barrier in another.

Conversely, policy enablers that may exist in one country may be missing from another and may not be captured by these 11 indicators. Many countries, for example, have begun to shift G2P payments into women’s accounts (Colombia is a successful example of this). This approach has created incentives for women to open formal bank accounts and gives them reasons to use them. This specific policy enabler isn’t identified as one of the indicators but clearly its existence in a market would facilitate women’s financial inclusion.

Many other factors that would influence the differences in results between countries such as the Philippines and Bangladesh include women’s labor force participation, women’s level of literacy and women’s roles as migrant workers. All of these factors would increase the demand side reasons for women to engage with the formal financial system. Labor force participation translates into receipt of a salary and often workers need a place to store those salaries and to make payments. The same is true for migrant laborers who often need the means to remit money to their families. Literacy is also associated with higher demand for financial services: the more education one has the more likely one will use formal financial channels. This is borne out in the academic literature; see, for example, this study. In the case of the Philippines, women’s labor force participation averages around 47 percent, whereas women’s participation in Bangladesh is only 36 percent. In the Philippines, literacy is essentially universal at 96 percent for women and 95 percent for men. In Bangladesh, women’s literacy is 70 percent as compared to 75 percent for men. Finally, in the Philippines, in 2018 there were over 1.2 million migrant female workers as compared to 1 million men, while in Bangladesh, women make up a very small share of the migrant labor force at only 13 percent as of 2013. In light of these very different demand-side issues, it’s striking that financial access for women in Bangladesh is nearly the same as that in the Philippines: 36 percent compared to 39 percent. What’s Bangladesh doing right despite these headwinds, and what can the Philippines do more to encourage usage of the formal financial system by both men and women?

Each country will need to define the conditions that will improve women’s financial inclusion.

Being able to identify a narrow set of policies or access to infrastructure that would promote women’s financial inclusion is appealing, and the EIU should be commended for making the effort to identify a set of potential policies. But the reality is that each country will need to define the conditions that will improve women’s financial inclusion based on barriers and opportunities unique to each country-wide market.