Earth Day was held on April 22nd to celebrate and promote environmental protection, including climate action. In the past decade, it has served as a momentary reminder of the need to respond to the causes and effects of climate change.

For much of the world, though, a reminder is hardly necessary. Dramatic shifts in weather patterns yield bizarre, destructive conditions at an increasing rate. The impact of these shocks on low-income people is profound as this population is more likely to be affected by and have difficulty recovering from climate shocks. The evidence shows that financial tools can help low-income people prepare for and respond to these negative events. However, more work needs to be done to develop appropriate financial products that help low-income households, entrepreneurs, and smallholder farmers mitigate and adapt to climate risk, which is why this topic is one of CFI’s four strategic pillars.

In an effort to build the evidence base on this topic, CFI launched a dipstick survey of urban MSME owners on their experiences with climate shocks. This is part of our broader four-country, longitudinal survey monitoring the impact of COVID-19 on MSMEs. The goal of the dipstick survey was to illuminate MSMEs’ resilience to climate change by examining the shocks that impacted them, the consequences of those events for their businesses, and whether there was a correlation between experiencing negative impacts in the recent past and the ability to recover from COVID-19 today.

CFI completed the first of these dipstick surveys with its panel of MSME owners in Lagos, Nigeria, in early March, and the data is striking, showing a large portion of owners have been negatively impacted by recent climate events and those that have been impacted are recovering more slowly from COVID-19 than their peers. This research is part of our partnership with the Mastercard Center for Inclusive Growth.

A quarter of MSME owners have had their business negatively affected by a climate shock in the past 5 years.

A coastal megacity, Lagos has grown dramatically in the past twenty years, with surrounding wetlands paved in favor of poorly planned urban development. Simultaneously, weather patterns have shifted, making Lagos hotter, encouraging the formation of massive thunderstorms with heavy rainfall. With no meaningful flood control system to speak of, these conditions have given rise to frequent, destructive urban floods. Rising sea levels and increased vulnerability to storm surges exacerbate the risk of flooding throughout the city.

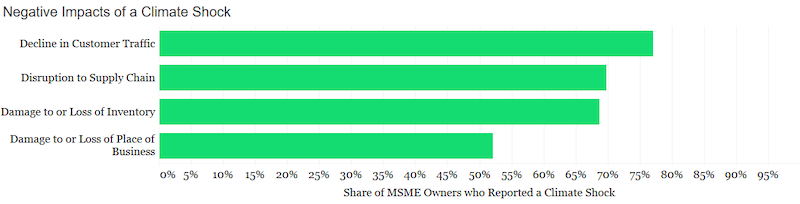

Over the course of the past five years, 24 percent of MSME owners in CFI’s survey reported that they had been negatively impacted by at least one of these trends, with flooding from heavy rains being the most common shock owners experienced. Of those owners who experienced a negative shock, most experienced a disruption to the supply of goods to their business and a reduction in customer traffic to their stores (see the graph below). Significant shares of respondents also reported longer-lasting, and likely more costly, impacts such as damage to or loss of inventory or their place of business.

MSME owners who experienced a major climate shock in the past 5 years are struggling more than their peers to recover from the COVID-19 pandemic.

A surprising finding from this survey was that there were no meaningful differences in the characteristics of owners—such as owner gender, industry, business size, and pre-pandemic profit level, among others—who experienced these shocks and those that did not, and yet these two groups are experiencing dramatically different outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic.

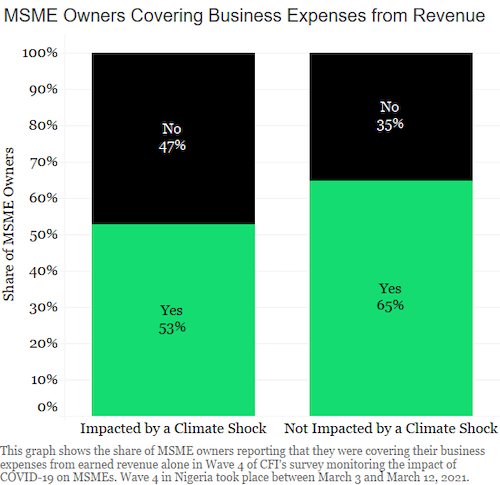

For instance, MSME owners who experienced a climate shock were less likely to report that they could cover their operating expenses from revenue. In addition, owners who did not experience a shock were much more likely to report that their profits were trending upward compared to their peers, suggesting a stronger recovery from the initial pandemic-induced downturn.

Their households were struggling too. Owners who experienced a climate shock were less likely to be covering household expenses from earned income than an owner who had not experienced a shock. And strikingly, of the respondents who reported that they were experiencing extreme household food insecurity, all of them had been impacted by one of these shocks in the past five years.

This is correlation, not causation — based on the survey design, CFI cannot say that experiencing a negative impact in the past five years caused an owner to be less resilient to the COVID-19 pandemic with certainty. However, there is a large body of research on the compounding effects of disasters on well-being — including livelihood opportunities, asset loss, and physical health — and the lack of resources available to low-income populations to recover from them. It is not hard to imagine that an MSME owner who leveraged her financial resources to recover from a flood is less likely to have resources available to respond to a future disaster.

There is data from the survey to support the hypothesis that it is harder for low-income households to leverage their portfolio of financial resources to respond to a series of shocks, even when those shocks are years apart. For instance, MSME owners who experienced a climate shock in the past 5 years reported they would be less likely to use credit, savings, or cash transfers from friends or family to recover from a similar shock in the future. The COVID-19 data shows that this phenomenon is in play currently: owners who experienced a climate shock saved and borrowed less often than their peers who had not been impacted by a shock in CFI’s most recent survey wave. They are sending money to and receiving it from their social networks at similar rates, though. Use of insurance is negligible in both groups despite strong evidence that it is an effective tool for helping people plan for and respond to economic shocks.

Stakeholders can help MSMEs build back better, but careful consideration will need to be given to the financial tools they need to make it through inevitable systems changes.

In the wake of COVID-19, there have been calls for communities to “build back better” by investing in development that makes them resilient to future disasters. For communities in Lagos, this data suggests that low-income entrepreneurs who have experienced a climate-related shock will need more support to build back better than their peers who have not experienced such shocks.

In the medium-term, this support will likely need to take the form of systems-level investments in infrastructure by the government to mitigate the risk of future shocks. Lagos needs improved flood control systems. But any large, public works project in densely populated areas is likely to disrupt MSME owners that live and work in affected communities. The government would need to consider how to keep an investment in resilient infrastructure from becoming another economic shock for these people. Offering grants or low-cost, government-sponsored loans to affected businesses during construction may help them survive.

FSPs, regulators, and policymakers will need to work together to ensure MSME owners have continued access to appropriate and affordable financial services.

In the meantime, financial service providers (FSPs), regulators, and policymakers will need to work together to ensure MSME owners have continued access to appropriate and affordable financial services. As climate science is mainstreamed into credit risk models and insurance underwriting, financial services will become more costly for low-income consumers living and working in risky areas. In their current iteration, certain financial products, like flood insurance, are likely to become unaffordable as the systemic nature of the risk grows. It will be critical for the government and the private sector to work collaboratively in such circumstances to ensure the supply of financial services to underserved communities. This could involve things like packaging government-sponsored flood insurance with private loans to de-risk lending and investment for FSPs and MSME owners, respectively.

This will not be easy to do. The government will need guidance on what policy measures are effective; FSPs will need to discover new, effective business models; and consumers will need additional support to ensure that they understand and are protected from risks associated with climate-focused financial products. These takeaways underscore the need for CFI’s focus on these elements as part of our climate agenda.

For us, studying climate risk will not be just an Earth Day affair: we will continue our dipstick surveys in Colombia, India, and Indonesia in the coming months to study MSME owners’ experience with climate shocks. Stay tuned for announcements of new data releases to CFI’s data dashboards. Follow us (LinkedIn, Twitter, newsletter) on our journey of learning and advocacy.