ESG frameworks provide standards and guidance for how companies should integrate the consideration of risks and opportunities arising from environmental, social, and governance factors into their practices at all levels. But could the implementation of the frameworks themselves become a source of risk or of opportunity for companies?

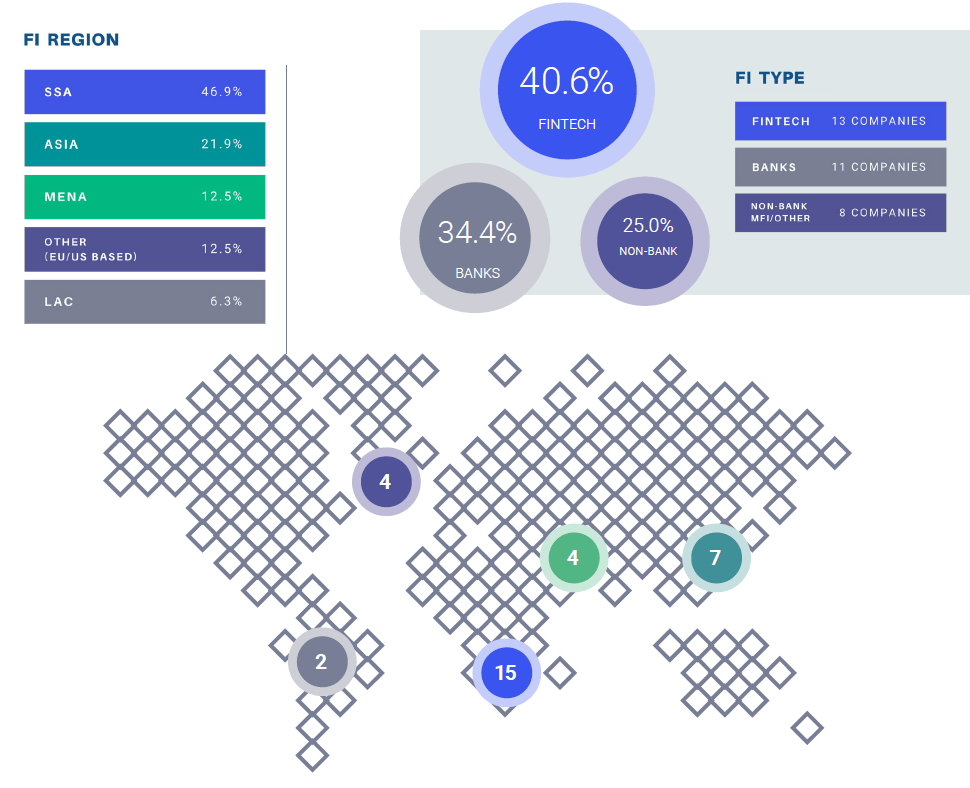

We set out to explore this question in a well-defined subset of companies: financial institutions operating in the ‘Global South’, that is, low- and middle-income countries. We engaged with leaders from 32 financial institutions, including banks, fintechs, and non-bank and microfinance institutions with a fairly even spread among them. They represented institutions of different scale—around two fifths were large with over a million current clients, one fifth were small with less than 50,000 clients, and the rest were in between. In a new report called Southern Voice in ESG, we seek to provide some answers to this question.

Why Is This Question Even Relevant?

The question about the potential implications of ESG frameworks is relevant because of the accelerating pace of adoption of ESG measures globally. In some places, ESG measures are known interchangeably as sustainability measures, although both terms are rather vague and ill defined. The pace has been driven by two channels—investors and regulators.

On the one hand, the proportion of institutional capital under some form of ESG mandate has continued to rise, especially in the Global North (high-income countries), so any entity seeking to raise capital there would likely be subject at least to questions. This would apply whether the capital is equity or debt, and especially if it comes from public development finance institutions who have by and large adopted ESG policies relating to their practices.

On the other hand, regulators have become an active channel for entrenching frameworks in domestic regulation, so that they are no longer voluntary but compulsory. While some Northern regulators have been especially outspoken on the issue, Southern regulators have increasingly paid attention. The Sustainable Banking and Finance Network now has 62 regulators from the global South at different stages of adopting the frameworks. And voluntary frameworks are becoming international standards: consultations on the new draft IFRS Sustainability standards S1 and S2 closed in July 2022, with the expectation that final standards in these areas may be issued in 2023. Regulators generally require regulated financial institutions as well as public companies to follow IFRS accounting standards, so the influence of standards like these is likely to be global.

The Frameworks Will Have Material Implications

Not surprisingly, our respondents already sensed the mounting pressures: almost 80 percent of the people with whom we spoke in the Global South expected that their depth and breadth of reporting would change in the next three years as a result of ESG pressures – in other words, that the frameworks would have a material impact. More than 70 percent said that it was ‘important or very important now’ to have capacity internally on ESG. However, only 7 percent described the current levels of skills and knowledge inside their organizations as adequate for their needs at present – more than half reported ‘some but limited’ or no skills in this area. They aren’t alone – ESG skills are in high demand but are scarce globally, according to this recent podcast.

“More than 70 percent said that it was ‘important or very important now’ to have capacity internally on ESG. However, only 7 percent described the current levels of skills and knowledge inside their organizations as adequate.”

What Are the Potential Risks or Opportunities?

The impact of the ESG frameworks is expected to be material in the next three years, and there is already a shortage of capacity to address them. How could the frameworks themselves be risks or opportunities? During our discussions, we saw the following risks and opportunities:

Potential risks:

- Diversion of skills and focus

- Costs to implement

- Distraction from other national priorities

- Constrained access to capital if not compliant

- Changed nature of impact from organization’s mission

- Strategic focus that is not aligned with institutional purpose

- Rapid adoption may be only skin deep: i.e. “ESG-washing” if the approach is compliance driven

Opportunities identified:

- Differentiation from competitors in capital raise

- Differentiation on staffing

- Implementing new ESRMs

- Resourcing for new areas of capacity-building

- Funding for new portfolio development

An issue of rising importance was the heightened emphasis on the ‘E’, with most associated indicators focusing on mitigation of climate risk. As one respondent put it, “The E has landed, the S is nowhere, and the G is hiding somewhere in the other two.” Most Southern financial institutions to which we spoke were ill prepared to report on climate risk measures, although they cared deeply about what some called ‘the S in the E’, that is, the adaptation and resilience indicators among vulnerable populations whom they served, many of whom live in the areas most exposed to the effects of climate change though their own carbon footprints are very small.

Which Is It — Risk or Opportunity?

So, what is the answer: are the emerging frameworks seen more as risks or as opportunities? Our sample indicated a mix of both. For example, when asked to indicate their level of agreement on a scale of 1 (fully agree) to 5 (fully disagree) with the statement: “ESG frameworks are on balance a positive force for our organization”, responses averaged 2.7, almost right in the neutral middle, with little difference between banks and non-banks. Responding to the statement “ESG frameworks encourage us to consider opportunities for value creation more than the need for compliance,” responses averaged a very similar 2.8. Similarly, “ESG frameworks create new reporting burdens which are disproportionate to the likely benefits” yielded an average of 3.1, right around the neutral midpoint. However, as one respondent told us, “Different frameworks may bring specific risks or opportunities, but overall, we see having an approach to sustainability is an imperative, not a choice.”

ESG Voice in the South

To date, most international ESG frameworks have been developed mainly under Northern leadership and pressure, reflecting the environmental and social priorities experienced there. This is quite different from earlier moves in areas of impact finance, like modern microfinance which was ‘born’ in the Global South and whose leading early practitioners like Grameen Bank’s Mohammed Yunus, BRAC’s Fazle Abed or Bancosol’s Pancho Otero were outspoken social entrepreneurs living and working there.

We sought to understand whether international ESG frameworks considered the needs and context of developing economies. The overall average score here reflected a range of views –with many neutral, perhaps because of lack of knowledge, but some strong divergence around this.

We asked all respondents to identify leading Southern voices with a distinct view on the issue, but received few suggestions. While there clearly is some Southern voice represented in most if not all of the major framework bodies like UNEP-FI or IFRS, there is less evidence at present of a distinctly Southern voice around these issues. However, as Southern-based financial institutions start to pay more attention to the issue of ESG framed in this way, new voices are likely to emerge with the interest and passion to engage locally, regionally, or internationally.

In the course of our discussions, we encountered the view that the impact of ESG frameworks may be less asymmetric by geography (i.e. whether based in the Global North or South) but by size of institution. Small and medium sized institutions have less capacity to hire new skills and absorb the resource costs than large ones, wherever they are based. A proportional approach to the introduction especially of compulsory frameworks is needed to ameliorate this risk.

What to Do About It?

Our aim at this stage was primarily to benchmark current reality as the basis of considering future actions. For example, almost half the respondents reported that they had no senior manager with a designated responsibility for sustainability, although one fifth already had placed someone in this role.

The possible strategic stance of a financial institution on this issue depends on how material the issue is, which will vary based on factors like client base, regulator attitude, extent of foreign funding, and the extent to which they believe ESG frameworks are locally influenceable. This will be a function of how much domestic regulators are influenced by international norms, and whether they are open to local adaptation.

Our findings point to several possible directions to mitigate risk and emphasize opportunities:

- Discussion and advocacy: While less than half of the institutions currently discussed ESG issues in the trade groups of which they are a part, almost double this number expressed interest in being part of discussions going forward. One positive example of proactive engagement is the work of FSDA supporting the piloting of Taskforce for Nature-Based Financial Disclosures, the next frontier within the ‘E’ of ESG, with a sample of large African FIs.

- Capacity building: There are many examples of courses being offered, in person and online, but most at present are developed by prominent Northern-based universities like Cambridge or Yale, or Northern professional bodies like the Institute of Environmental Management and Assessment. There are opportunities to support regional offerings to spread awareness and knowledge.

- Technical support: Several institutions directly asked about technical support offerings. However, in a recent training session for Kenyan banks run, experts from UNEP-FI said that, due to the fast-moving pace in this area, many consultants may not have more knowledge than the bank staff themselves. Local technical support may need further capacity building to be helpful.

Conclusion

Southern financial institutions clearly believe that international ESG frameworks matter and that they will affect their activities in some way, negative and/or positive, in the next three to five years. As the numerous voluntary frameworks converge and start to harden into standards and even local regulation, it is important that Southern financial institutions have voice and can participate meaningfully at all levels: both shaping international frameworks and especially adapting them for regional and local implementations. The urgency of climate action for mitigation in large emitting nations risks provoking a ‘rush to regulate’ Southern financial institutions whose clients may not themselves be major emitters of CO2, though their livelihoods are highly vulnerable and in need of adaptation support. In the presence of conflicting priorities and constrained local resources, it will take time to regulate appropriately. However, supporting Southern financial institutions to adapt to these priorities over time will likely improve ESG outcomes for these institutions and for the many vulnerable clients they serve.