Although the CARES (Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security) Act has mobilized a whopping $293 billion to provide one-time economic impact payments to American households, many are ineligible for this federal support due to their immigration status or living in a mixed-status household. Cities, counties and states across the United States are stepping in for these residents by bridging the gap with cash transfer programs of their own.

Beyond the inherent complexity of quickly establishing a safe and efficient cash distribution program, serving this marginalized population presents specific challenges. First, local governments need to identify and enroll beneficiaries from a population that generally lacks official identity documentation and can be difficult to reach. Second, in addition to being undocumented, this population is often unbanked or underbanked, raising questions about how cities and counties can safely deliver financial stimulus in a cost-effective manner. Third, data protection is high stakes for this population, which tends to be at greater risk for financial fraud or exploitation, as well as targeting by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE).

Given these challenges, how should US cities design cash transfer programs to serve undocumented communities?

With support from Open Society Foundations, CFI identified more than 70 examples of city- and county-led municipal identification initiatives (active, inactive, and proposed) that sought to address challenges residents face in obtaining government-issued forms of identification. For marginalized and vulnerable populations—such as the undocumented, those experiencing homelessness, and the elderly—a lack of official identification makes everyday tasks like accessing social services or opening a bank account difficult.

Cities that have established these programs, particularly those that have sought to leverage them to advance financial inclusion, provide several lessons to cities facing similar challenges while establishing cash assistance programs in response to COVID-19.

Local Partnerships are Key to Reaching Marginalized and Vulnerable Populations

Cities and counties have successfully engaged marginalized and vulnerable residents by working with trusted community-based organizations (CBOs).

CBOs are embedded within the communities they serve, have a deep understanding of their needs, and act as trusted intermediaries between residents and public officials. Collaboration with CBOs has been central to the operations of IDNYC, New York City’s successful municipal identification program. CBOs have been involved in every phase of the project, including planning and design, implementation, communications and outreach, and evaluation. Modeling a grassroots campaign, IDNYC has been intentional about working with CBOs to engage excluded communities, contributing to the success of the program: well over a million IDs have been distributed so far, the most of any program in the country.

In Washtenaw County, Michigan, one local CBO—Synod Community Services—serves as the lead advocacy organization for its public-private partnership-based ID Task Force and heads all community outreach efforts related to the Washtenaw ID. In addition to working with local businesses and other institutions to provide benefits and discounts for cardholders, Synod works with the county clerk’s office for mobile enrollment of homebound residents and has partnered with the county sheriff’s department for remote enrollment of incarcerated individuals about to reenter society.

Given the success of this approach for identification programs, it is no surprise that many cities are opting to work through CBOs to implement cash assistance programs. The most successful ID programs CFI researched included collaborations with CBOs that continued throughout the programs’ lifecycles, as opposed to just utilizing them as one-time distribution channels. Cash assistance programs should follow the same model by including CBOs from the outset in program design—from enrollment to cash distribution—to ensure the programs meet the specific circumstances of the communities they are trying to reach.

Getting Cash to the Unbanked: IDs, Fee Structures and More

Getting cash to unbanked populations is difficult. A lack of identification and a lack of trust in the government and formal financial institutions are two of many challenges this group faces. In the current environment, where limited physical interaction is important, the logistics of getting cash to the unbanked is even more complicated. Municipal ID programs have laid the groundwork to help overcome some of these obstacles, and they provide cautionary tales for addressing others.

To advance financial inclusion objectives, many city and county identification programs have partnered with financial institutions that have experience serving unbanked and underbanked populations. IDNYC, for example, has 13 financial service providers (FSP) and community development financial institution (CDFI) partners that accept IDNYC as a primary or secondary form of identification for account opening. In a 2016 evaluation of the IDNYC program, 12 percent of cardholders reported they opened a bank or credit union account using their municipal IDs. The City of San Francisco’s Office of Financial Empowerment works to extend financial access to the unbanked by promoting Bank On guidelines, which include guidance to FSPs about accessible identification requirements for migrant communities.

To advance financial inclusion objectives, many city and county identification programs have partnered with financial institutions.

Despite efforts like these, identification is just one of many challenges in reaching unbanked and underbanked communities. Many organizations interviewed by CFI noted that migrant communities often have less knowledge of the formal financial system in the US and are intimidated by unfamiliar institutions and processes. Residents may be wary, if not outrightly distrustful, of city officials or financial institutions due to negative past experiences.

In partnership with a local CBO and the Mexican Consulate, Los Angeles worked with Citi to create financial empowerment “windows” within the consulate to provide “free, culturally and linguistically competent financial counseling and education resources onsite” to Mexican immigrants and the broader Latino community in the city. These types of efforts to provide information and guidance to individuals in their language and within a context of trust are critical to reaching migrant communities.

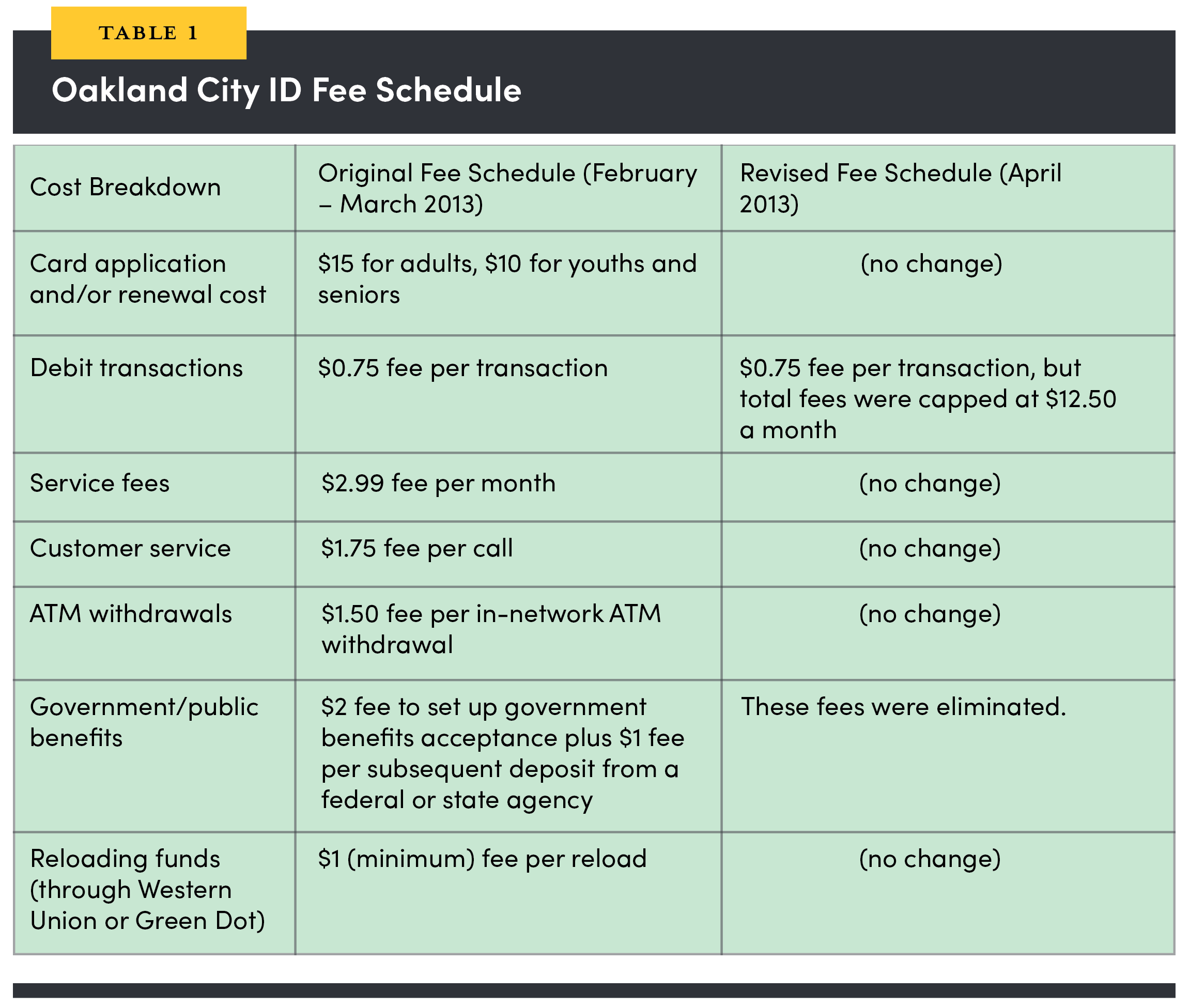

By contrast, the Oakland City ID is one example of how poor product-market fit can exacerbate distrust between cities, advocates, migrant communities, and FSPs. The Oakland City ID was a municipal ID program that was also intended to help meet the financial needs of unbanked and underbanked residents by offering a smart ID with a prepaid debit card function issued by a third-party provider at no cost to the city. When the Oakland City ID was launched in February 2013, the program again came under intense scrutiny for its fee structure, which would have had an outsized impact on the city’s most vulnerable residents; critics advocated for lower fees and stronger consumer protection measures and safeguards.

Although Oakland moved to reduce fees within weeks, the Oakland City ID program arguably highlighted the numerous challenges of successfully executing an initiative that aimed to meet the needs of vulnerable residents for other cities. (Ultimately, the prepaid debit card functionality was eliminated entirely). By focusing on finding a vendor that would run the program at no cost to the city rather than considering the full impact of the prepaid debit card fees on cardholders, Oakland made an unpalatable tradeoff that, among other missteps, depressed uptake of the municipal ID.

This cautionary tale underscores the delicate balancing act of thoroughly deliberating different financial products and responding quickly to meet residents’ needs. In the rush to respond to COVID-19, public officials should consider these examples and understand the potential tradeoffs between speed and a well-crafted approach that leverages local partners and accounts for the specific contextual challenges of reaching unbanked individuals.

Protecting Sensitive Data

For undocumented residents, fear of the federal government amplifies concerns about the risks of receiving a municipal ID or interacting with formal financial institutions. There is widespread concern among advocates that city-led initiatives like municipal IDs or financial inclusion programs can pose a significant risk for the undocumented community: providing ICE with another data source by which to identify and track users.

These fears are not unfounded. Legal challenges to municipal ID programs in New Haven, Connecticut, and New York City have sought access to data on cardholders. Although neither legal challenge was successful, they led to changes in how each program collects and stores data.

One representative for a CDFI in the Northeast US underscored undocumented clients’ pervasive concern that their money wasn’t safe from the federal government, noting “I’ve had discussions with customers about how I can’t tell them the federal government will never seize their money. I can’t guarantee that won’t happen.” Former officials in Los Angeles suggested that these concerns contributed to the failure to launch a municipal ID program citywide. In a national political environment outwardly hostile to these communities, these officials were extremely concerned that sensitive cardholder information collected by the city could potentially be accessed by federal authorities involved in immigration enforcement. There have been recent examples to bolster this concern. In Washington state, officials at the Department of Licensing gave driver’s license applications to ICE, which used the data to bolster cases against presumed undocumented immigrants despite an executive order from the governor aimed at limiting state officials’ support of immigration enforcement.

Many of the emerging cash assistance programs have data and monetary flows that are different from municipal IDs. Cities transfer money to CBOs, who transfer it to undocumented migrants. The migrants cash checks, withdraw money from ATMs, or spend it at merchant locations depending on the distribution model. In return, undocumented migrants share information with the CBOs that provide basic reporting back to cities. These data flows leave digital footprints that are different and, in some ways, more complex and expansive than those left behind by municipal ID programs.

Yet these digital records may not be the greatest risk facing the undocumented community. CFI’s research suggests that the primary risk to this population comes via interactions with law enforcement agents. In other words, as a recent leader at a CBO told CFI, “the path to deportation begins with police interactions,” and those interactions are often initiated in the real world. For instance, a city council member from a large Midwestern city indicated in an interview with CFI that ICE targeted undocumented migrants by physically monitoring municipal ID enrollment locations. In New York, there were isolated incidents of municipal ID holders trying to access federal facilities using their cards. They were arrested after not having their cards accepted as valid forms of identification.

CFI’s research suggests that the primary risk to this population comes via interactions with law enforcement agents.

These examples make clear that, beyond being a fiduciary agent for the public and private funds being used in these cash assistance programs, cities must consider their role in protecting CBOs and undocumented migrants.

Looking Ahead

CFI identified 17 COVID-19 cash assistance programs in a preliminary review of gray literature. These programs are being rapidly established, using emerging payment platforms in some cases, and are responsible for pushing out large sums of money.

For instance, the Angeleno Campaign, capitalized by the Mayor’s Fund for Los Angeles and private donations and administered by Accelerator for America and the city’s Housing and Community Investment Department (HCIDLA), was launched to provide immediate and direct financial assistance to the city’s neediest residents. Leveraging Mastercard’s City Possible payment platform, the Campaign has worked to quickly distribute no-fee prepaid debit cards ranging from $700 to $1,500 to eligible households through HCIDLA’s 16 nonprofit-run Family Source Centers.

In Austin, Texas, the city council has created the Relief in a State of Emergency (RISE) Fund to provide immediate relief to vulnerable, lower-income residents, including direct financial assistance to those ineligible for state or federal aid. The RISE Fund, capitalized through a reallocation of $15 million from Austin’s Emergency Reserve Fund, has been distributed to registered social service providers with a demonstrated history of success in reaching vulnerable community members. These CBOs, in turn, have disbursed financial assistance through gift cards or prepaid debit cards ranging from $1,200 to $5,000 per qualifying household. In both examples, demand for financial assistance is much larger than the supply of funds.

The economic impact of COVID-19 is likely to sustain demand for these types of cash assistance programs. As municipalities launch new programs and scale others, municipal IDs offer three key principles for effective program design:

- Local partnerships are critical: CBOs should be brought in at the earliest stages of program design and be partners through implementation. They should not be considered merely a pass-through for distribution.

- Financial products need to be customer-centric: Reaching undocumented and marginalized communities will require close attention to user-centric product design and marketing, including addressing issues of trust, familiarity with the US financial sector, and product cost.

- Data privacy and protection is vital: Gaining the trust of individuals who most need support will require certain provisions to ensure their information is protected. Cities need to assess the risks to their constituents based on financial fraud, data breaches, subpoenas, and enforcement actions.

CFI will continue researching the many cash transfer programs emerging to address the impacts of COVID-19. The focus of this research will be on the following topics:

- how programs are ensuring user data is protected;

- what mechanisms or resources are in place to protect recipients and provide recourse in the event of fraud;

- what best practices from state, national, or humanitarian cash assistance programs cities can adopt to improve their programs; and

- how these initiatives could be leveraged to achieve larger social objectives, including financial inclusion.