As you drive into Quetzaltenango, the largest city in Guatemala’s western highlands, you pass a large statue. The migrant depicted in “Homage to the Migrant of Salcaja” (the name of the local municipality) stands 30 meters high, wears a backpack, and faces north. The statue pays tribute to the thousands of Guatemalan migrants who, despite the risks and the costs, have left this corner of the country to seek opportunities elsewhere.

The number of international migrants from Guatemala tripled from nearly 462,000 to almost 1.4 million people between 1995 and 2020. A recent survey shows that in 2021, 43 percent of Guatemalan households expressed the desire to migrate, five times the percentage in 2019. Among the reasons for this – food insecurity, unemployment, and desire to send remittances home – one that underlines and exacerbates these issues is climate change.

People who are already marginalized tend to experience a greater impact from climate-related events.

The effects of climate change are not felt equally, and people who are already marginalized – such as women, low-income populations living in rural areas, indigenous groups, and smallholder farmers – tend to experience a greater impact from climate-related events. The impact of climate change is growing and Guatemala is particularly affected because of its dependence on agriculture. In 2018, a delay in the rainy season in the Central American Dry Corridor – spanning El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua – damaged 70 percent of subsistence farmers’ first harvest and ruined 50 percent of their second harvest. Agriculture employs more than 70 percent of the rural population in Guatemala, and because of increased temperatures and shifts in the rainy season, thousands have been forced to leave their homes as they are unable to feed their families.

Guatemalan migrants are predominantly from rural areas – the same areas that have been highly impacted by climate-related disasters. The share of international migrants from rural areas in Guatemala is twice that of urban areas, and most migrants from Guatemala to the U.S. are from the western highlands, motivated to leave because of natural disasters such as the droughts of 2014, 2015, and 2018. This is true across the region: evidence from Mexico suggests that rising temperatures and weather shocks associated with climate change increased the likelihood of internal migration from rural areas to urban areas as well as international migration.

The populations most impacted by climate change also tend to be financially vulnerable: 60 percent of rural Guatemalans say they would be unable to come up with emergency funds. Only 10 percent of the loans offered by Guatemalan financial institutions are dedicated to agriculture and just a fraction of that is invested in adaptive practices to respond to climate change. So how can financial services work better for these climate-vulnerable populations?

Remittances Help Families Make Ends Meet But Are Not the Full Answer

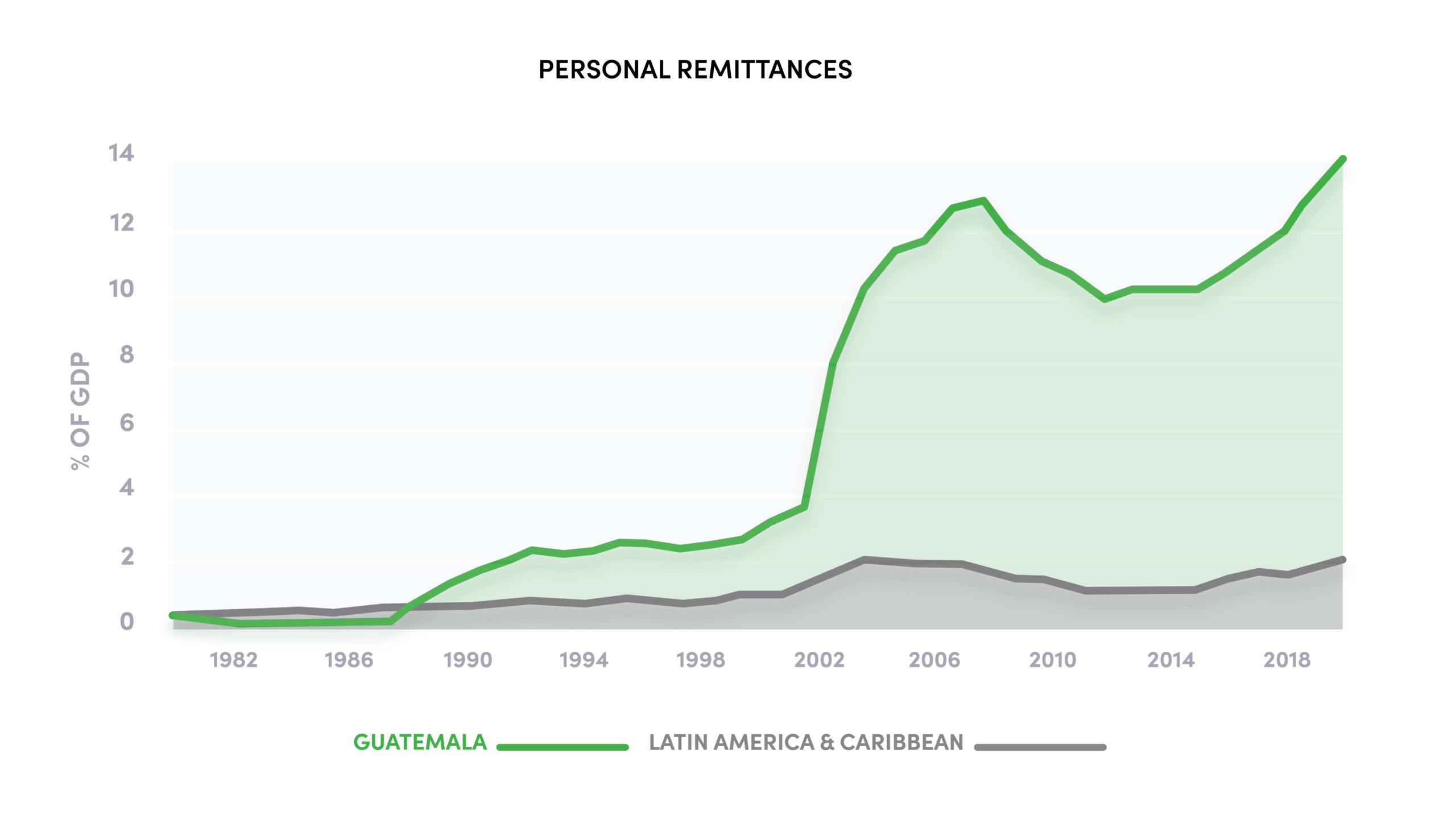

Between 2000 and 2020, remittances exploded from 3 to 14.7 percent of GDP in Guatemala and represented seven times the average in Latin America and the Caribbean in 2020. Three in 10 Guatemalan households receive remittances with an average monthly amount of $350, according to the most recent data published in 2020. Recipients are disproportionately rural and most are located in the north and western highlands of Guatemala.

Remittances from migrants are a critical source of income for many families in Guatemala and are relied on to cover food expenses (57 percent), education (10 percent), or household construction (8 percent). Among the remittance recipients in Guatemala, a large share are women (69 percent), live in or are at risk of poverty (88 percent), and have attained primary education or less (77 percent). However, only 3 percent of recipients use remittances to invest.

In a country where the losses in agriculture due to natural disasters were around $2.4 billion between 1992 and 2011, and where migrants spent $1.2 billion dollars to travel to the U.S. in 2021, there are opportunities to encourage Guatemalans to use their remittances to invest in forward-looking practices that build resilience to climate change. Financial services are needed that channel remitted funds into investments in sustainable agriculture and support forest-based livelihoods, while putting women at the center given they are the primary recipients of remittances. While remittances can be a key tool for resilience and risk management, there is also a role for them to support adaptation, by linking diaspora funds to investments in climate-smart agriculture and sustainable rural enterprises.

Remittances can support adaptation as well as resilience and risk management.

In Guatemala, 325 out of more than 1000 cooperatives provide savings and credit services and focus on MSMEs, particularly small-holders. We believe financial services have a key role to play in supporting resilience, through products like insurance and informal social support systems that build on Guatemala’s strong cooperative movement. Financial services also play a critical role in underpinning a just transition for rural populations. One example of this is the Guatemalan government’s social protection initiatives Pinpep and Probosque schemes that provide financial incentives for tree-planting and reforestation. CFI is working with The Nature Conservancy and other partners to explore these issues.

Imagining a Constructive Role for Financial Services

As far as we know, the Migrant of Salcajá isn’t a real person but rather a representation of the thousands who have made the treacherous journey. To make the trip north, the migrant is likely to have informally borrowed up to $17,500 to pay smugglers, known in Guatemala as “coyotes”. If the migrant reaches the U.S. border and finds work, it can take time to find the funds to repay the debt. And if the migrant doesn’t reach the U.S., they remain indebted. The combination of lack of economic opportunity and predatory moneylending can lead to dangerous debt traps.

Imagine if the money flowing back from the current generation of migrants could change the incentives for the next generation, encouraging them to stay and build climate-resilient livelihoods.

But imagine if Guatemala’s financial system offered the services needed to invest in resilient rural livelihoods, to adapt to changing climatic conditions, and to diversify into new opportunities in agro-processing. Imagine if the money flowing back from the current generation of migrants could change the incentives for the next generation, encouraging them to stay and build climate-resilient livelihoods. There is a long way to go, but it is increasingly clear that improving the way that financial services work for Guatemala’s smallholders has a role to play in the dual challenges of climate change and migration.