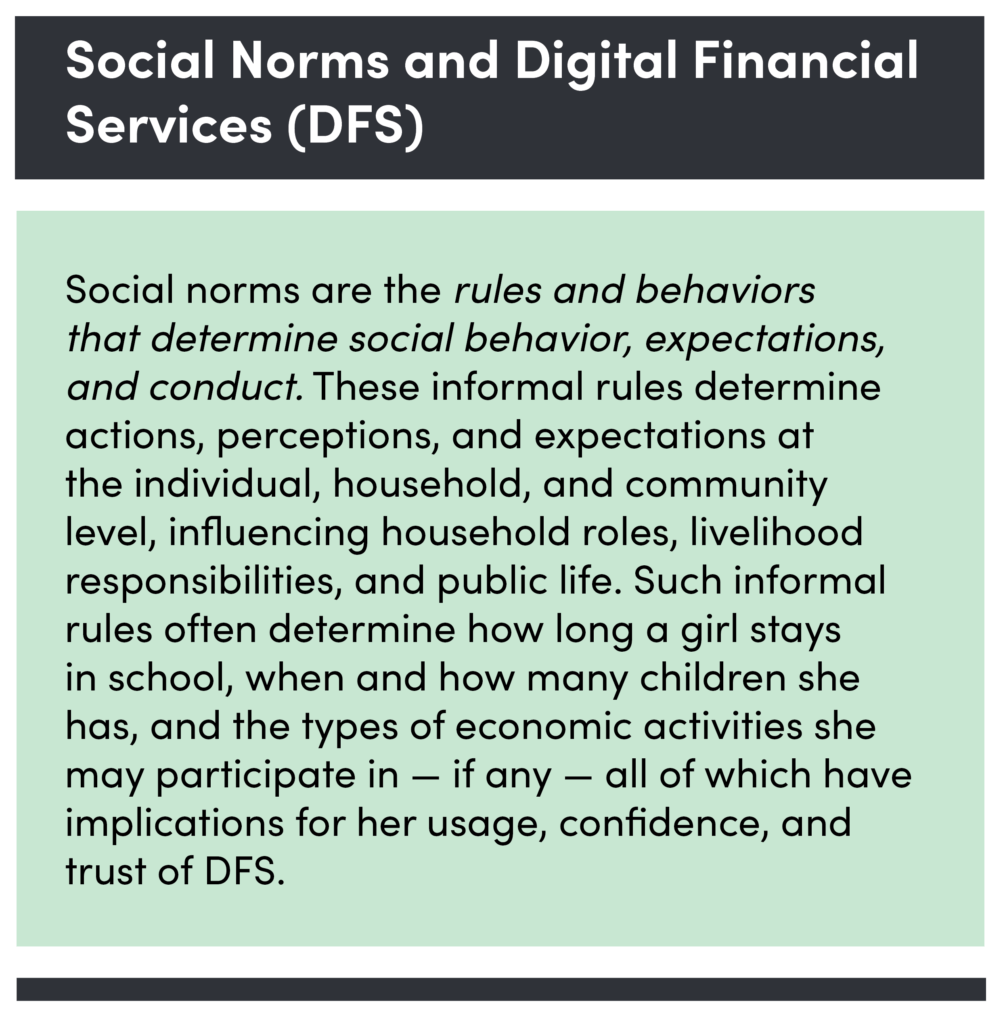

For low-income women, digital financial inclusion offers an opportunity to upend entrenched gender inequalities by entering spheres from which they have been otherwise excluded. Financial services delivered via mobile phone can bridge the last-mile gap, bringing financial tools and services directly to women where they work and live. However, women are underrepresented customers of digital financial providers and platforms. Well-established impediments such as cost, literacy, and normative barriers (that shape the way people behave and expect others to behave) prevent low-income women from using such services at the same rate as men. These demand-side constraints, combined with a dearth of sex-disaggregated customer data, leave most fintech firms without a clear picture of women’s wants and needs for digital financial tools. As such, most mass-market tools are not designed with women in mind.

Demand-side constraints and a dearth of sex-disaggregated customer data leave most fintech firms without a clear picture of women’s wants and needs for digital financial tools.

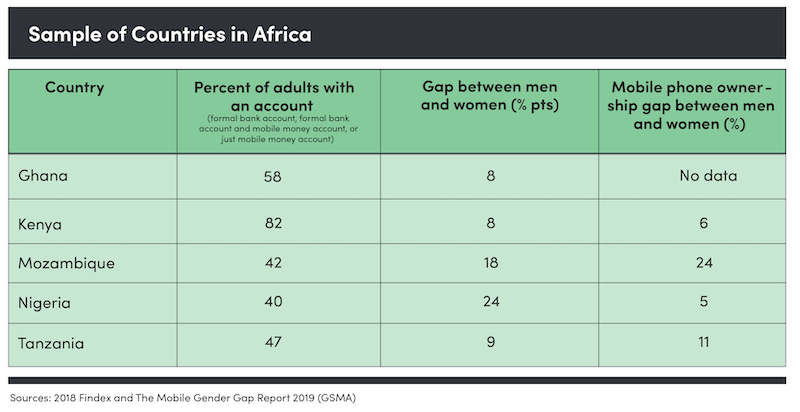

It’s not just digital financial inclusion: Fewer women than men have access to formal bank accounts and mobile technology. Globally, 65 percent of women, compared with 72 percent of men, have bank accounts, while 197 million fewer women own a phone than men, according to the GSMA Mobile Gender Gap Report 2019. Regional variations make these gaps more striking. In Sub-Saharan Africa, for example, home to many promising emerging market fintech innovations, the mobile gender gap is 15 percent, while in South Asia (including Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh) the gap is 28 percent. Further, access to formal bank accounts is extremely low across Africa. For example, the gender gap in account ownership in Kenya, according to the table below, looks to be only about 8 percentage points. However, the gap widens when adults with only a mobile money account are disaggregated from formal bank accounts and mobile money accounts. Around 65 percent of men in Kenya have both a formal bank account and mobile money account, while only 50 percent of women do. Interestingly, the gender gap in adults with only a mobile money account is reversed; more women than men have only a mobile money account, likely because the barriers to entry are lower than for a formal bank account. This trend can be seen throughout Africa.

Given the gender gaps in bank account ownership and mobile technology, it is not difficult to see why many fintech firms do not have visibility on how to better serve women. With fewer women users, and little to no sex-disaggregated data around how women’s use of and needs for these products differ from men’s, it can be difficult to identify low-income women’s needs and preferences. Excluding women is often unintentional — “gender-blind” design is thought of as an inclusive strategy. If “bias” is not baked into the design, the thinking goes, then anyone who wants to use the product can. Unfortunately, the opposite is true. Gender-blind product and platform design strategies allow products to flow in the way they always have: into the hands of those who are already in the marketplace and who make the decisions about who else can benefit from or access these products. A “gender-intelligent” or “gender-aware” approach, on the other hand, seeks to overcome women’s specific constraints through data-driven design based on market research in order to create distinct customer value. And the numbers in the table demonstrate that men disproportionately benefit from bank accounts and mobile technology.

We show the potential of gender-aware design, and how to design for specific needs and constraints of women, while accounting for the norms that define their lives.

This brief examines design principles employed by two fintechs, Paycode and Extramile, working in Sub-Saharan Africa. We show the potential of gender-aware design, and how to design for specific needs and constraints of women, while accounting for the norms that define their lives. These two examples provide insights into why intentionally focusing on women can bring benefits to this largely untapped market and how fintechs can design products that meet women’s needs. Only by improving women’s meaningful use of financial services through concerted efforts to close the gender gaps will low-income communities and households begin to see potential economic benefits from inclusion, benefits that will also flow back to the providers that serve them. It is vital that fintechs move away from gender-blind or -neutral strategies toward gender-aware and even transformative strategies that bake in access pathways for potential customers with limited knowledge or physical mobility. Gender-blind design is not gender-neutral.

Fintechs in Sub-Saharan Africa and a Gender-Blind Approach

According to data collected by Inclusive Fintech 50 (IF50) — a competition founded by MetLife Foundation and Visa, with support from Accion and IFC, and additional funding from Jersey Overseas Aid & Comic Relief — only six of the 403 fintech applicants claimed women as their target customers. Most applicants selected “rural households,” “MSMEs,” or “low-income individuals” as their target market. This belies the fact that all of these fintechs reach women — for many of the IF50 winners, women make up nearly 50 percent of their customers. Indeed, women make up a large proportion, if not the majority, among those market segments.

This trend continues among the IF50 fintechs focused on the African continent. Of the 2020 winners in Africa, the product and livelihood focus ranged from mobile banking, water and utility payments, mobile-based crop insurance, and a range of credit and savings products directed at low-income populations. For example, OKO secures the income of farmers of unirrigated farms in Mali and Uganda through a mobile-based crop insurance that automatically compensates them if they suffer from adverse weather.

Within the profile descriptions of the 15 IF50 winners based in or delivering services in Africa, their customer segments were primarily described as “unbanked,” “underserved,” or “low-income.” A few mentioned women, but most called out their customers by their lack of access to financial services. Only three out of the 15 mention women in their key problem statement, while eight mention “unbanked” populations. Identifying women as their target market is not a requirement, even if women make up nearly half of their customers. But by calling out their target customers in terms of livelihood rather than by gender, these fintechs may assume that every “unbanked” person or MSME has the same level of access to their products. This is rarely, if ever, the case.

If these fintechs do not see women as their target market, how do they reach so many women? Gender-blind product design does not translate into complete exclusion — but it does mean that a product is more likely to reach and work well for certain segments of customers, namely men. Gender-blind design can be seen in mass-market items like car seatbelts and mobile phones as well as digital financial tools such as chatbots with basic financial literacy information or a mobile wallet. In some cases, targeting certain livelihood segments may lead fintechs to see where their design is ill-suited for their women customers and make adjustments. In 2019, UNCDF hosted a design sprint in Zambia for fintechs seeking to increase their female customers — the finalists all designed and modified their products after interacting with women customers. In other cases, women may in fact be a central target segment, but aspects of a woman’s life, such as normative constraints (like care responsibilities or intra-household decision-making), and thus the product doesn’t achieve desired inclusion or impact.

Inclusive Fintech 50 Winners: How Can They Design for Women?

To further illustrate this point, below are profiles of two Inclusive Fintech 50 winners that both have similar missions to serve underserved, unbanked rural communities with access to payments or financial services. While a majority of their customers are women, neither fintech set out to specifically target them. Were these fintechs to focus further on their female clients’ needs and preferences, they could potentially reach more women and provide them with beneficial services.

Paycode

Headquartered in South Africa, Paycode offers last‑mile delivery financial services technology solutions to unbanked populations offline in real‑time. Paycode links government social payments, mobile money, or payments to farmers or rural recipients without a formal bank account. The company addresses three key needs among rural populations: lack of formal identification, little to no connectivity, and high cost of service delivery. To do this, Paycode offers end users a biometric-linked smartcard which can be used at point-of-sale (POS) machines. Since a vast majority of end users live in remote, rural places, Paycode brings the POS to rural villages by putting cash machines on the back of pickup trucks. This branchless banking model is designed to work entirely offline — end users confirm their identity, access their accounts, and withdraw their funds with no internet or mobile connection. Their transaction data is uploaded when the Paycode employee reconnects to the internet.

Several aspects of Paycode’s delivery model and design unintentionally meet some of women’s unique needs. First, introducing a new technology in a rural setting, particularly one involving so many moving parts (fingerprints, smartcards, POS, etc.) can be tricky. Building trust among users can take time. Before going into a community, Paycode scopes the village to understand the needs of potential customers as well as identify and train locals who can act as facilitators on behalf of Paycode. When ready, Paycode provides all the necessary equipment and systems to onboard a customer and issue them with a biometric smart card on the spot. The onboarding process takes a total of seven minutes.

Several aspects of Paycode’s delivery model and design unintentionally meet some of women’s unique needs.

Another innovation involves the biometric ID itself. End users are onboarded using their fingerprints — to verify their identity and proof of life. End users select a finger to act as their primary ID. They also select up to three individuals to act as a back-up in case their fingerprint is unreadable (many smallholder farmers have rough hands and fingerprints can be tricky to obtain). In addition to selecting proxies for access, end users also select an “alert” finger — a risk mitigation strategy that silently triggers a false low balance in their e-wallet while simultaneously alerting Paycode’s system of a potential theft. This risk mitigation strategy was designed to mitigate the threat of gun violence, but it also provides safety and control for female end users if their male partner attempts to co-opt their funds.

Both these aspects of Paycode’s business, and particularly the alert finger, meet women’s specific needs, even if they weren’t designed with that intent. Control over income or assets can be particularly challenging for women in light of informal rules that, for example, may expect a woman to hand over her money to her male partner. The alert finger enables her to navigate economic violence that could potentially escalate into physical violence while maintaining control over her assets.

Extramile Africa

Extramile Africa targets savings groups in Nigeria by offering increased security of their funds and the ability to earn interest on their savings. Informal savings groups such as rotating savings and loan associations (ROSCAs) are common throughout the world and have mostly female membership. These groups are an informal way for women to save, collect lump sums of savings, and access a form of credit.

Extramile targets two segments of women: smallholder farmers who make up the ROSCAs and women-run microbusinesses who make up two-thirds of their merchant network. The savers receive free and ongoing extension services, including advice at planting, harvest, and selling. The assistance is meant to ensure market linkages for farmers to sell their goods, which can be difficult or unpredictable for many smallholders. The savers transact — make deposits as well as withdrawals — with any Extramile merchants, who tally their savings on a unique ID card and are paid a small sum to take all the cash weekly to a bank, a sometimes two- to four-hour bus ride.

Savers must have a basic feature phone on which they receive SMS confirmation messages about their deposits. The use of technology increases transparency and security among group members, mitigating group infighting around transactions and savings totals, as well as improving financial accountability among savers. Extramile also created an app on which their merchants, who must have smartphones, can provide offline deposit taking and withdrawals. Extramile also uses the app to identify farmers or microbusinesses in each community with whom to invest part of the total savings by analyzing savings transaction data linked to each user. Profits from the investments are shared out every six months, with savers and farmers or businesses receiving 40 percent each, and Extramile receiving 20 percent as part of a sustainability strategy. This investment scheme enhances the economic resilience within communities.

To gain the trust of communities served, Extramile targeted community leaders and held community-wide meetings where they provided food and offered agricultural technical assistance. Extramile banking partners provided POS machines that Extramile brought to the community meetings to familiarize the community as well as train merchants how to use them. Their farmer co-ops and groups are targeted for onboarding as well as for financial management information around their savings behavior — for example, given that their savings are leaving their hands, they are told to keep cash on hand for daily expenses.

Extramile addresses the insecurity of women’s funds through placing some of it in bank accounts

Like Paycode, some of Extramile’s design choices benefit women. Savings groups are primarily made up of women and are a critical, if insecure, means to save cash outside of homes. Extramile addresses the insecurity of their funds through placing some of it in bank accounts, improves group members’ knowledge through financial and agricultural education, and even provides another income source through community investments. Targeting female merchants is similarly beneficial as these are usually lower-resourced businesses than male-run counterparts. Extramile improves female merchants’ technological capacities and adds income sources by paying merchants to make the trek to urban centers and through profit-sharing.

Adding a Gender Lens

Both Paycode and Extramile have been successful at embedding a deep understanding of rural livelihoods into their product design. Through mobile cash machines or providing a secure way to save, these two businesses clearly seek to address the informality and related vulnerability of their customers’ lives. They also clearly understand that building trust is foundational to their work, addressing it with community engagement or on-the-spot proof of concept. Given the fact that women make up a majority of both companies’ clients, going further to understand women’s lives, economic needs, and constraints will increase both the impact of their services and the growth opportunities for their businesses. Fintechs are uniquely positioned to take a gender-intelligent approach to design: they are close to their customers, collect all sorts of customer data which they can use to build products for women’s needs, and have the flexibility to pivot and experiment when necessary.

Going further to understand women’s lives, economic needs, and constraints will increase both the impact of their services and the growth opportunities for their businesses.

For Paycode, that might look like providing parallel investments in financial and digital capability in ways to enhance their primary business of cash disbursement. Due to the constraints they face, women are often less literate or lack key skills compared with men that are needed to increase their incomes or yields from their agricultural labor. Financial capability is critical to women’s and households’ long-term financial health. Partnering with financial experts or training local agents to provide financial information — ideally linked to a financial service — and digital literacy that may encompass uses of technology beyond Paycode’s specific services would greatly increase women’s inclusion and increase their capability to use Paycode’s products. Digital capability may also include designing for the fact that mobile phones are often a shared resource, and thus any messaging or nudges might be seen by more than just the intended recipient.

Building out organizational partnerships to meet the full range of customer needs is critical, and this has become essential during the COVID-19 pandemic for fintechs and customers alike. Partnering with a microfinance institution or savings association with formal financial linkages may help build healthy behavior and provide a customized experience for Paycode’s end customers. Paycode and Extramile could partner with agricultural small and medium enterprises (agri-SMEs) that often provide training and also financial services (i.e., credit) to farmers. Customer transaction data from both fintechs can be used as an alternative credit score for women to get access to capital they are disproportionately excluded from. Extramile could offer this type of service by leveraging data on savings behavior for lines of credit to be reinvested into the communities. Finally, both fintechs could seek out ways to address some of women’s non-economic constraints, such as the intra-household power dynamics around household budgets and expenditures that often hand control over to male partners. Addressing these dynamics as it pertains to economic decisions takes specific training, and Paycode and Extramile could partner with trained facilitators to have information sessions with customers. These types of parallel investments have been known to improve women’s financial inclusion and overall household economic well-being. Women’s financial inclusion is only as deep as women’s ability to make decisions over their financial assets and see those decisions through to their completion.

Both fintechs could seek out ways to address some of women’s non-economic constraints, such as the intra-household power dynamics around household budgets and expenditures that often hand control over to male partners.

Gender-blind digital financial technology can and does reach women customers. However, embedding women’s unique needs and constraints into product design enhances women’s inclusion, ensuring their lived experiences are accounted for, thus making a financial product more meaningful to each customer and more valuable for the business. Fintechs like Paycode and Extramile have already done the difficult work of innovating to reach these last-mile populations — they are in the ideal position to make adjustments to their design that account for their female customers’ wants and needs. By gathering information on their female clients’ financial constraints, habits, and dreams, they can strengthen their impact on individual clients and their communities and take their businesses to new heights.