This is the second installment in CFI’s Series on Resilience: The Unfinished Business of Financial Inclusion. Part one of this series made the case for a stronger role for inclusive insurance.

Resilience has come to occupy an increasingly important place in the financial inclusion sector’s shift from access and usage toward outcomes. As the field has matured, the focus has moved beyond whether people hold accounts or use digital payments, toward whether financial services help households and micro and small enterprises (MSEs) withstand shocks and sustain progress over time. This turn has been shaped by a growing body of work, particularly in the contexts of climate change and financial inclusion, including the World Bank’s flagship analysis on Rethinking Resilience, CGAP’s Resilience for All report, and CFI’s own work linking inclusive finance to climate and environmental shocks.

Measurement has played a central role in this shift by enabling resilience to be observed and compared across countries and population segments. Much of the empirical work on resilience has relied on measures that are observable, comparable, and scalable across contexts. For example, access to emergency funds within seven or thirty days have become widely used proxies, in part because their measurement is embedded in global surveys such as the Global Findex and enable cross-country benchmarking. These measures have surfaced an important reality: many households and small firms remain one shock away from distress even as formal inclusion expands. At the same time, they also highlight the limits of what measurement alone can capture about how resilience is built and sustained in practice.

While resilience is now widely understood as multidimensional, the systems meant to support it remain fragmented. A broadly accepted definition of resilience emphasizes the capacity of households and firms to anticipate, withstand, and recover from shocks while sustaining progress over time. The defining element in this formulation is the presence of shocks, which can originate from many sources, including climate events, health emergencies, digital and cyber threats, income disruptions, and failures in physical or social infrastructure.

Each of these risks follows different transmission channels and calls for different forms of preparedness and response. Financial resilience plays a connective role because many shocks ultimately translate into financial stress, yet not all risks are financial in origin, nor can they be addressed through financial tools alone. In practice, households and small firms experience these shocks as interconnected and compounding rather than isolated. When risks interact, resilience cannot be built through siloed interventions. In the absence of shared infrastructure that links risks, behaviors, and responses across domains, resilience is often left to individuals to assemble on their own, even when the sources and consequences of shocks span multiple actors and systems.

Taken together, these developments point to a central challenge for the next phase of outcome-oriented financial inclusion. While the measurement of resilience has advanced significantly, the agenda for building resilience remains far less developed. Knowing where resilience is fragile does not, on its own, indicate how financial services should be designed, how public resources should be targeted, or how private and public actors should coordinate their responses. This brief argues that advancing a resilience-building agenda requires rethinking resilience as an investable form of capital, identifying incentive mechanisms that reward preventive and adaptive behavior, and, most importantly, building shared infrastructure that links risks, behaviors, and rewards across domains and actors.

Why Resilience Remains Undersupplied

A wide range of evidence suggests that resilience is not only unevenly distributed, but systematically undersupplied relative to the risks households and small firms now face. The frequency and diversity of shocks are increasing. Recent global surveys show that more than half of adults worldwide have encountered digital scams, with roughly one quarter reporting direct financial losses. World Bank research estimates that around one fifth of the global population is at high risk of exposure to climate-related risk, and that the expected impacts of climate change on the bottom 40 percent of the income distribution are, on average, about 70 percent larger than for the population as a whole. Yet indicators of financial resilience have remained largely flat. The Global Findex shows that in 2024, as in 2021, only about 56 percent of adults in low- and middle-income economies could access emergency funds without difficulty. Insurance coverage remains particularly limited. Nearly 90 percent of people in low-income countries have no form of private insurance, leaving households and small enterprises highly exposed to shocks that are becoming more frequent, more varied, and more costly.

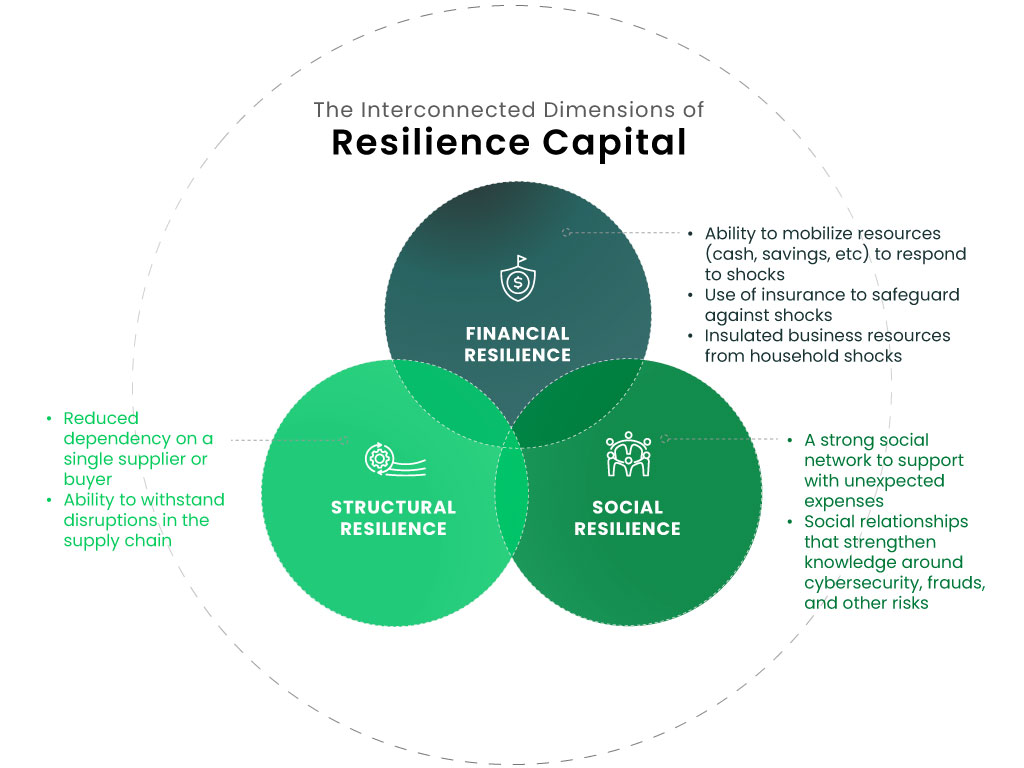

In Small Firms, Big Impact, a large-scale study on micro and small enterprises, we took an initial step toward unpacking what resilience means for small businesses across five cities: Addis Ababa, Delhi, Jakarta, Lagos, and São Paulo. Rather than equating resilience solely with emergency liquidity, we looked at three interconnected dimensions. First, financial resilience, in the familiar sense of liquidity, savings, and the ability to mobilize resources when needed. Second, structural resilience, capturing how dependent firms are on single buyers or suppliers, and how vulnerable they are to disruptions in those relationships. Third, household and social resilience, recognizing that shocks often travel through the household balance sheet or through care responsibilities and then into the business. An entrepreneur whose household can absorb a health shock without liquidating business assets is in a different position from one who cannot.

Across the five cities where we conducted our research, it became clear that no single dimension could account for how entrepreneurs withstand and recover from shocks. At the same time, the study underscored gaps in our understanding of resilience. Two challenges continue to shape how resilience is operationalized in the financial inclusion ecosystem.

First, resilience remains embedded in siloed delivery models. Products addressing savings, credit, insurance, payments, climate adaptation, or digital security are typically designed and delivered separately, leaving users to assemble their own safety nets across providers and systems. This fragmentation places a high coordination burden on households and small enterprises, particularly in moments of stress when resilience matters most. Recent thinking on integrated approaches to resilience, including Payal Dalal’s articulation of a financial services stack of the future, highlights this gap. It underscores that resilience depends not only on access to individual products, but on how services, incentives, and information flows function together when shocks occur. An effective framing of resilience therefore needs to reflect how risks interact and compound across systems, not only how they are absorbed financially.

Second, resilience has remained primarily a measurement construct rather than a guide for action. Over the past decade, the sector has become more sophisticated at tracking the pulse of resilience, yet far less progress has been made in determining what should be done when indicators move in the wrong direction. If we see that emergency liquidity is falling in a population, how should we diagnose why, and what guidance can be offered to strengthen the capacity to withstand shocks? Moving from measurement to strategy requires an apparatus that links diagnosis to priorities, something the field has not yet built.

Building Resilience Capital: Aligning Economics, Incentives, and Infrastructure

Strengthening resilience as a form of capital requires progress on several fronts at once. Measurement has advanced, and new evidence has clarified the types of pressures households and small firms face. However, the frameworks that guide action remain incomplete. We argue that a more ambitious agenda requires development in at least three areas. First, a clearer microeconomics of resilience. Second, an incentive architecture that rewards preventive and proactive action. Third, the digital and institutional infrastructure needed to link resilience behaviors with the actors who benefit from them. Together, these elements form the building blocks of a coherent architecture for resilience capital.

If resilience is to become a form of capital rather than a diagnostic category, it needs a clearer economic interpretation and a structure for understanding how it is produced and depleted. A useful starting point is the World Bank’s seminal work on the “Triple Dividend” of resilience, which reshaped global thinking by showing that investments in preparedness reduce losses when shocks occur, support smoother economic performance, and generate development gains even in the absence of shocks. These insights justified major public investments in early warning systems, safer infrastructure, and climate change readiness.

The challenge now is to articulate the equivalent logic at the micro level. National dividends ultimately depend on the behaviors of millions of households and small firms whose decisions shape how shocks are absorbed and how quickly recovery occurs. CGAP’s earlier work helped open this conversation by emphasizing that resilience rests on micro-foundations: the daily capabilities, social networks and behavioral constraints that shape how people anticipate, withstand, and recover from shocks. It also urged the sector to move beyond narrow financial definitions toward a more comprehensive understanding of what enables stability in practice.

A microeconomic framing begins with the question of what type of good resilience is. Investments in resilience generate clear private returns, since those who invest in flood protection, digital security, health buffers, or diversified suppliers experience fewer losses and shorter interruptions. Yet resilience consistently generates benefits beyond the individual. Lenders experience fewer arrears, insurers face fewer claims, governments carry lower emergency expenditures, and supply chains remain more stable. In some domains, resilience takes on public good properties. When more firms adopt safer digital practices, the entire ecosystem becomes less vulnerable to fraud or cascading breaches. When small businesses prepare for climate shocks, local markets remain more stable.

A growing set of global analyses is now examining the return on resilience investments as an economic asset, not only a protective measure. A recent white paper by the World Economic Forum in collaboration with McKinsey and members of the Resilience Consortium finds that resilience preparedness is now seen as a key driver of competitiveness and innovation in emerging markets. While only a minority of firms, roughly one in five, report being fully prepared to face shocks, those that are better prepared experience fewer prolonged disruptions and recover more quickly.

Complementing firm-level and macro perspectives, recent research points to consistently high returns on preventive investment in resilience and adaptation. Systemiq’s Returns on Resilience analysis finds that scaling climate and resilience investments in emerging markets could generate over 280 million jobs by 2035, unlock a resilience market of up to USD $1.3 trillion annually by 2030, and deliver benefits that are on average four times larger than costs, with annual returns around 25 percent. Evidence from the World Resources Institute, drawing on more than 300 adaptation projects across 12 countries, shows that every USD $1 invested in climate adaptation yields over USD $10 in economic, social, and environmental benefits over a decade. Returns are particularly high in sectors such as health, water, and urban infrastructure. Similar findings on the ROI of resilience were identified by Earth Security in the context of mangrove investments.

Yet these high returns do not materialize automatically at the level where most resilience decisions are made. Understanding the return on resilience for individual households and MSEs requires accounting for how risks compound across domains, where climate shocks, digital threats, income volatility, and health events interact rather than occur in isolation. At this level, resilience investments are shaped by short planning horizons, liquidity constraints, limited information, and weak signals that preventive action will be rewarded. These constraints help explain why many entrepreneurs in our research strengthened their practices only after experiencing losses, even when earlier, cross-cutting investments would have reduced exposure across multiple risks.

Understanding the economics of resilience is only the first step. The more difficult task is to influence investment behavior. MSEs cannot be expected to shoulder the full cost of preventive action when the benefits accrue to many others. A well-designed incentive architecture is therefore essential, especially in environments where margins are thin, liquidity is limited, and shocks are frequent.

Incentives for resilience are not new. Countries have experimented with approaches that reward preventive action in domains ranging from health to climate to digital security. Mexico’s Prospera and Brazil’s Bolsa Família demonstrated that conditional transfers can shift household behavior in ways that improve long-term wellbeing. India’s Swachh Bharat Mission lowered the cost of investing in sanitation and achieved large improvements in health and productivity. Kenya integrated crop insurance into its fertilizer subsidy program, linking productive investments and climate protection in a single package. Singapore co-financed cybersecurity tools and audits for small businesses, dramatically reducing the cost of adopting safer digital practices. These examples show that incentives can be designed to influence preventive behavior at scale.

However, the current landscape is fragmented. Each sector deploys its own incentives, often without awareness of how risks interact. Climate programs focus on adaptation, health systems focus on continuity of care, digital authorities focus on cybersecurity, and financial regulators focus on credit stability. Entrepreneurs experience these risks simultaneously, yet the incentives available to them are not coordinated. This patchwork makes it harder for small firms to assemble the full set of capabilities needed to prevent shock-related losses.

A coherent incentive architecture would do three things. It would reward preventive and proactive action rather than only compensating recovery. It would align incentives across public, private, and philanthropic actors based on shared benefits. And it would support the accumulation of resilience capital over time, rather than relying on one-off interventions. The examples cited above demonstrate that incentives can shift behavior when designed well. The challenge is to bring them together in a way that aligns with the multi-dimensional nature of risk.

Incentives cannot function effectively without the infrastructure that links behavior to reward. Resilience develops across domains that are interconnected, and the benefits are distributed among many actors. A small business that improves its digital security not only protects itself, but also lowers risks for lenders and fintechs that depend on safe transactions. A shop that invests in flood protection not only protects inventory, but also reduces losses for insurers and stabilizes the livelihoods of workers. These shared benefits create a rationale for cost sharing, but only if the underlying investments can be verified, recognized, and rewarded.

Designing infrastructure that supports shared incentives is not new in finance. Credit bureaus and collateral registries created data systems that allow lenders to reward repayment behavior and manage portfolio risk. Emerging green credit registries in China use a similar concept. Households and firms that invest in energy efficiency or emission reductions can receive better loan terms or financial rewards. These systems create a link between behavior and benefit that aligns private and public interests.

Resilience could evolve in a similar direction. Investments that strengthen resilience, such as maintaining long-term savings, purchasing insurance, improving digital protections, or preparing for climate risks, could be recognized through systems that allow financial providers and public actors to offer reduced fees, better pricing, or targeted support. Such infrastructure would require trusted verification mechanisms. Self-sovereign digital wallets are one possibility. Extending the functionalities of e-money wallets used primarily for storing value and making payments, self-sovereign wallets can hold verifiable credentials. They could confirm that an individual completed a cybersecurity training, paid insurance premiums, invested in climate preparedness, or met certain resilience criteria. These capabilities would allow multiple actors to participate in incentive design, each contributing support toward behaviors that benefit them.

Importantly, this agenda does not imply transferring responsibility for resilience onto individuals or small firms. Nor does it suggest that private investments can substitute for public investments in physical infrastructure, safety, or social protection. As highlighted in CFI’s recent work on the hidden trade-offs of digital public infrastructure, the role of shared infrastructure is not to replace markets with government-run or donor-dependent mechanisms, but to strengthen the conditions under which markets can function more effectively. In the context of resilience, shared infrastructure can help close persistent incentive gaps by making resilience-enhancing behaviors more visible, verifiable, and rewardable. Rather than displacing existing public or private roles, it enhances coordination across them, allowing financial institutions, platforms, insurers, and public actors to align incentives around prevention and preparedness while operating within their respective mandates.

This is an emerging space with many complexities. It will require piloting, interoperability standards, and careful consideration of privacy, governance, and inclusion. Yet without this type of infrastructure, the incentive architecture needed for resilience capital will remain incomplete. If resilience is to be treated as a form of capital, the systems that recognize and reward its accumulation need to be built.

The Work Ahead

Building resilience capital will not hinge on a single framework or a single product innovation. It will depend on progress along three fronts: clearer economic reasoning about why resilience is undersupplied, incentive structures that reward prevention rather than response, and shared infrastructure that allows resilience-enhancing actions to be recognized and acted upon in real time. This challenge is becoming more urgent as financial systems evolve. Agentic AI and automated decision-making are beginning to shape many areas of the financial sector, from how credit is allocated to how risks are priced, and how support is triggered during disruptions. Without deliberate design, these systems risk reinforcing short-term efficiency gains at the expense of long-term resilience. With the right data and incentives, they could instead become powerful tools for anticipatory action, helping households and small firms prepare for shocks rather than merely react to them.

The agenda ahead is therefore as much about governance and design choices as it is about technology. Policymakers and regulators face decisions about how resilience-related data can be shared responsibly, and where public intervention is justified to correct market failures. Financial institutions and platforms must decide whether resilience remains peripheral to underwriting, pricing, and product design, or becomes a factor that actively shapes how services are delivered. Donors and development partners have a role in supporting experimentation, reducing early risks, and ensuring that emerging architectures do not privilege only those with the most data or digital capacity.

None of this will be resolved quickly. The risks that shape the lives of small firms cut across climate, digital safety, health, infrastructure, and markets, and no single actor can address them alone. But the direction of travel is becoming clearer. As financial inclusion continues its shift toward outcomes, resilience can no longer remain a measurement construct or even a conceptual framework with unclear links to policy actions. Advancing this agenda will require pilots, evidence, and collaboration across public, private, and philanthropic actors. This brief is intended as a step toward that next phase of work.

Acknowledgements: The authors thank Payal Dalal of the Mastercard Center for Inclusive Growth and Peter McConaghy of the Office of the United Nations Secretary-General’s Special Advocate for Financial Health for their thoughtful feedback and insights. Any remaining errors are the authors’ own, and the views expressed do not necessarily reflect those of the reviewers or their organizations.

This brief was developed with the support of the Mastercard Center for Inclusive Growth.

Photo credit: Huy Thoai