Past crises have taught the microfinance sector a lot about weathering storms, and microfinance institutions (MFIs) are once again facing challenging times. This case study is part of a series that CFI, in partnership with the European Microfinance Platform (e-MFP) and the Mastercard Center for Inclusive Growth, is publishing to revisit tales of tough times and resiliency in five markets — Azerbaijan, Bosnia and Herzegovina, India, Nicaragua, and Palestine — and discuss how MFIs, with the help of their investors and other stakeholders, emerged and thrived. The lessons learned from these cases will be compiled and examined in a forthcoming report, Weathering the Storm II, a follow-up to the first edition published in the aftermath of the global financial crisis a decade ago. The hope is that these lessons will be applicable to not only the COVID-19 response, but to future crisis responses as well.

During the final months of 2008, as the world was entering what would be the worst economic crisis of the past half-century, Senad Sinanović, CEO of Partner Microcredit Foundation in Bosnia and Herzegovina, was contemplating the future.

A year earlier, he and his staff had celebrated Partner’s 20th anniversary. Partner was founded following the tragic war that marked the breakup of Yugoslavia, which had itself been assembled from the ashes of the Austro-Hungarian Empire 90 years earlier. It was in the country’s capital, Sarajevo, that WWI began, with the assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand. On his frequent work visits to Sarajevo, Sinanović sometimes passed by the plaque marking the site of the “shot heard round the world,” along the way stepping on the Sarajevo Roses — red-painted shell marks on the pavement, remnants of the Bosnian war of the 1990s. In that corner of the world, history can seem omnipresent.

But it wasn’t history that was on Sinanović’s mind. He was worried about how the financial crisis would impact his clients, his institution, and the broader microfinance sector in the country. The path ahead concerned him greatly. The situation was unfolding against a backdrop of high liquidity in the sector. A strong period of growth of the main MFIs during the second half of the 2000s, as well as a new regulatory framework for microcredit, contributed to the high confidence of donors and funders, who responded by pouring large amounts of funding into the market.

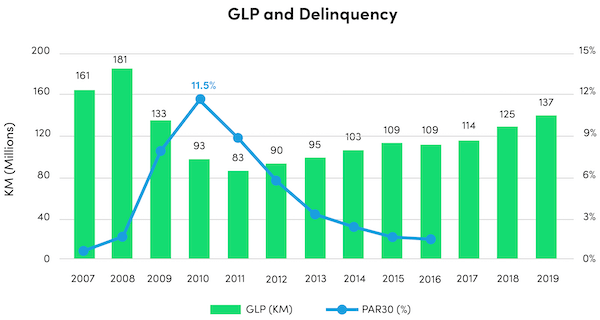

In 2008, the tiny country of Bosnia and Herzegovina, with a population of 3.7 million, was the second biggest destination worldwide, behind Peru, for foreign capital investment in the microfinance sector. In that market, Partner was (and still is) one of its leading MFIs, with the third largest by gross loan portfolio at about 181 million convertible marks (abbreviated KM), or about USD$106 million, and the second largest in number of active borrowers, at 63,500.

High liquidity may be a blessing during growth periods, but it quickly becomes a curse when loan demand contracts and all that cash sits in a bank, yielding no income. The deep recession in Bosnia brought about by the global financial crisis strongly affected the micro and small enterprises in the country, resulting in less appetite for investment, and thus for the business loans provided by the microcredit sector.

High liquidity may be a blessing during growth periods, but it quickly becomes a curse when loan demand contracts and cash sits in a bank, yielding no income.

Those same challenges also lowered clients’ ability to repay their existing loans. In a context of intense competition between MFIs and widespread multiple borrowing — which was difficult to trace since the use of credit bureau data was still incipient — this predictably resulted in severe loan delinquency problems and credit losses across all MFIs. The poor lending standards of several MFIs also undermined the sector’s reputation, further legitimizing non-repayment of loans even beyond what might have been expected from the economic downturn alone.

Dealing With High Liquidity

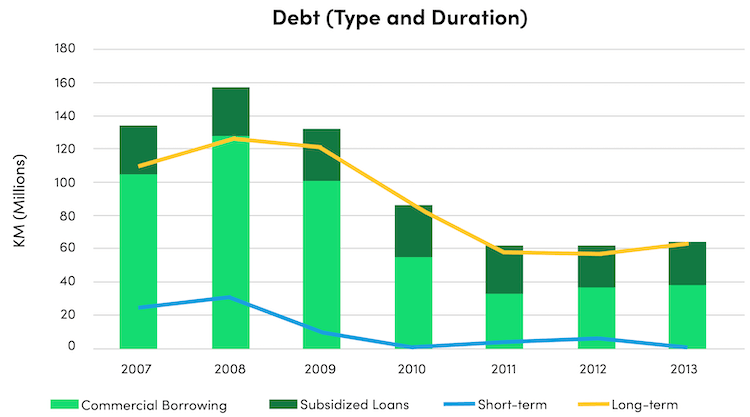

Partner had, by the end of 2008, a total debt of 156 million KM, broken down into 10 outstanding short-term loans with local banks and 23 long-term loans from foreign social and development investors. While the overwhelming majority of these were market-rate loans, Partner also had subsidized loans, including a 6 million euro loan from a bilateral public funder.

Some of the loans had just been disbursed when the crisis began to unfold, leading to a situation where Partner was sitting on a pile of money that it could not lend out, and thus could not generate income, even as the interest due on the loans continued to accrue.

To limit interest losses, especially on its more recent and expensive loans, Sinanović tried to give the money back, asking to prepay the loans ahead of schedule. However, this was not welcomed by all investors, and some needed to be persuaded to accept the money and terminate the contracts without penalties. This process included a meeting in April 2009 with lenders at the Microfinance Centre (MFC) conference in Belgrade, organized by a group of Bosnian MFIs, including Partner. Facing the reluctance of some investors to accept early loan prepayment, one of the Bosnian CEOs questioned if their behavior was consistent with social investing, which helped change investors’ minds. During the period of crisis, and in the following years, Partner’s short- and long-term debt fell significantly. By the end of 2011, its total debt was down 61 percent from its peak in 2008.

Getting Ahead of Events

While reducing excess liquidity solved a part of Partner’s problems, the MFI was still facing strong, serious challenges in its loan portfolio and the consequences of escalating credit and market risks.

During 2009 and 2010, Partner’s portfolio contracted by nearly 50 percent off its 2008 peak, and while it has been recovering steadily since then, as of 2019, its portfolio remains 25 percent smaller than it was over a decade ago, at 137 million KM ($78 million).

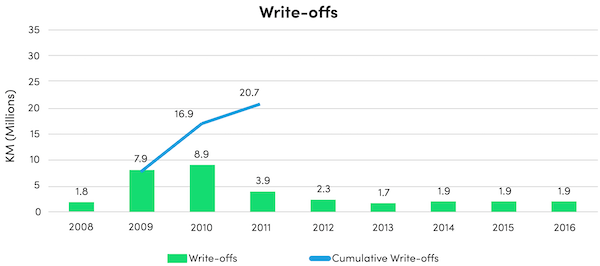

Beginning in 2008, delinquency levels grew rapidly, peaking at 11.5 percent in 2010. Partner also took an aggressive approach to writing off loans it saw as non-recoverable. Between 2009 and 2011, the MFI wrote off 11.4 percent of its 2008 gross loan portfolio (GLP). While high, these credit losses were modest in the context of the Bosnian microfinance crisis. Three of Partner’s major competitors experienced cumulative write-offs of 25 percent or more of their peak 2008 portfolio (according to the authors’ calculation using MIX Market data).

Nonetheless, Partner’s portfolio quality was worrying, and during the early months of the crisis, Sinanović knew already that Partner would breach many of its debt covenants with its lenders. Together with Partner’s board of directors, Sinanović decided to get ahead of events and provide lenders all the information available on the context of the crisis, the reputation issues affecting the sector, and the exact situation of the MFI. For this, Sinanović and his staff prepared a detailed, 13-page memorandum outlining the impact of the crisis on Partner, its clients, and the Bosnian microfinance market, as well as Partner’s response up to that point and planned next steps. The memo also included extensive monthly data and ratios pertaining to Partner’s portfolio and financial situation. This document was sent to all 17 creditors in April 2009, when the crisis was still in its early phase.

Sinanović and his staff prepared a detailed, 13-page memorandum outlining the impact of the crisis.

In this way, Partner’s transparency helped gain lenders’ confidence and, at the same time, effectively created the reporting template for all individual creditors. This early transparency helped Partner avoid being flooded with multiple and diverse requests for information by lenders and gave Sinanović and his team the space to focus on containing repayment problems in its portfolio.

Midway through the crisis, after extensive conversations with like-minded MFIs in the country and with support of outside stakeholders, Partner went further. In 2010, together with two other MFIs, EKI and Mi-Bospo, Partner created U-Plusu. This non-profit financial management advisory center aimed to tackle client over-indebtedness and improve the public image of the institution and the sector by providing financial education and mediation services between clients and financial institutions, especially in cases of multiple borrowing.

Despite the serious impact from the crisis, with credit losses accompanied by steep drops in lending and profitability (ROE decreased from 24 percent in 2008 to -5 percent in 2009), Partner managed to keep the situation under control throughout, and its solvency was never at risk. In fact, despite the large provisions and eventual write-offs, Partner’s equity only slightly decreased during the crisis period (from 43 million KM to 41 million KM).

Partner’s solvency was never at risk and its equity only decreased slightly.

Partner’s ability to weather the storm was closely linked to a process of foresight and preparation led by Sinanović and the MFI’s directors. It started with swift adaptation to a significant decrease in loan demand, both in terms of credit offer and operational structure, and an aggressive strategy regarding write-offs, while getting rid of excessive liquidity and being proactive and transparent in its communications with creditors. All this helped Partner ready itself for what would be a sustainable — albeit smaller — future.

What are some dos and don’ts and key success factors that the microfinance sector can learn from the Partner case? CFI’s forthcoming report, Weathering the Storm II, will draw on lessons from Partner and cases from microfinance institutions in four other markets: Azerbaijan, India, Palestine and Nicaragua. See also the original Weathering the Storm report from 2011.