Past crises have taught the microfinance sector a lot about weathering storms. Microfinance institutions (MFIs) are once again facing challenging times. This case study is part of a series that CFI, in partnership with the European Microfinance Platform (e-MFP) and the Mastercard Center for Inclusive Growth, is publishing to (re)visit tales of tough times and resiliency in five markets – Azerbaijan, Bosnia and Herzegovina, India, Nicaragua and Palestine – and discuss how MFIs, with the help of their investors and other stakeholders, emerged and thrived. The lessons learned from these cases will be compiled and examined in a forthcoming report, Weathering the Storm II, a follow up to the first edition published in the aftermath of the global financial crisis a decade ago. The hope is that these lessons will be applicable to not only the COVID-19 response, but to future crisis responses as well.

Spandana started in 1998 as a microcredit program of an NGO. It quickly became one of the bellwethers of the country’s microfinance industry, offering small group loans to predominately low-income women without the need for collateral. When Spandana was incorporated as a non-bank financial company/microfinance institution (NBFC-MFI) in 2003, it was the largest microfinance institution in India and the sixth largest in the world. In the early 2000s, Spandana was growing rapidly and began exploring a path to an initial public offering (IPO).

The state of Andhra Pradesh (AP) had become one of the most competitive microfinance markets in India during this time. As more commercial MFIs grew, they competed with the state government’s Self-Help Group-Bank Linkage (SHG) program. The SHGs had access to capital from the banking system and worked with millions of underserved women by helping them save small sums and take out loans.

The AP government started to become uneasy with the outsized impact and influence of commercial MFIs, however. Increased competition led to excessive lending, with many clients taking out multiple loans from both SHGs and commercial MFIs. Average household debt in AP rose to about INR 65,000 compared to a national average of about INR 70,001. The MFIs were accused of harassing customers for repayment. The suicide rate spiked, and the state government began attributing some of these suicides to excessive lending by the MFIs and coercive loan recovery practices.

The Andhra Pradesh government started to become uneasy with the outsized impact and influence of commercial MFIs.

In order to rein in the alleged coercive recovery practices of the commercial MFIs, the state government passed the AP Microfinance Institutions (Regulation of Money Lending) Act in October 2010. The ordinance barred MFIs from collecting payments at certain locations, such as a borrower’s home or place of work. The regulatory authority also set interest rate caps and mandated stringent reporting guidelines.

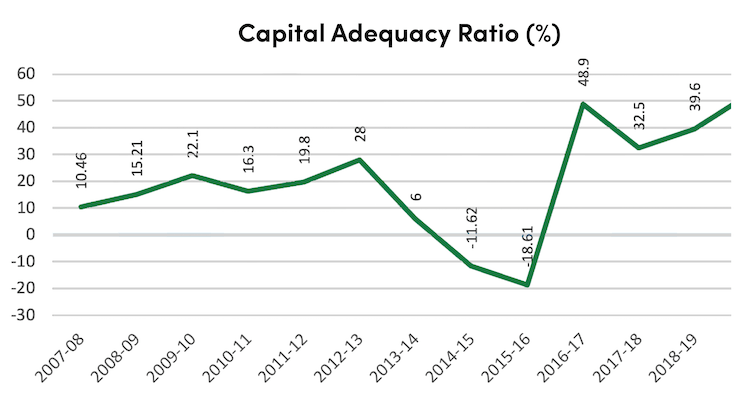

Clients misconstrued the ordinance to justify non-repayment of loans owed to the MFIs with no serious repercussions. Within a month, the loan repayment rate had dropped from 99.89 percent to 1 percent. An estimated INR 70 billion in loans in the state, from about 6.25 million accounts, had come under stress. This led to severe cash flow problems for the MFIs in the region. In the end, the ordinance caused some MFIs in the state to close and declare bankruptcy. For Spandana, even though it had sufficient capital adequacy (with equity of INR 4.85 billion), the unfolding crisis meant severe financial stress and cash flow problems.

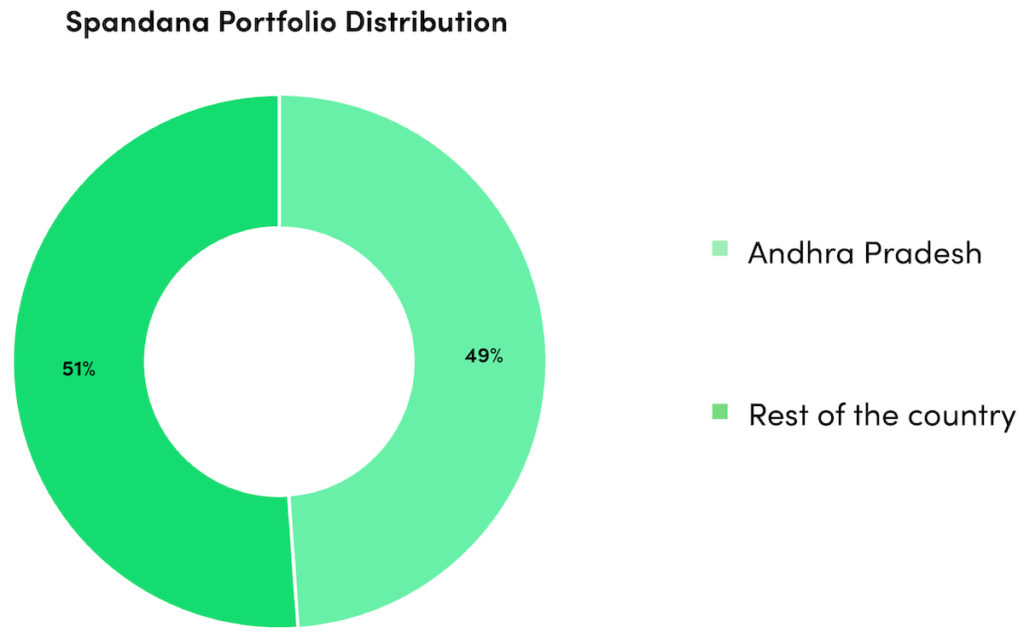

At the onset of the crisis, loans in AP accounted for about half of Spandana’s portfolio. In addition to its customers, the livelihoods of the firm’s employees were also at stake: Spandana employed 7000 in AP and had 850 branches operating there.

After the shock of the ordinance rippled through the microfinance ecosystem, Spandana felt it had no choice but to take the case to the court. While it was good news that their case eventually reached the Supreme Court, it meant a long wait, and Spandana’s management was forced to suspend operations in AP and scrap their IPO plans while the court heard their case. Knowing it couldn’t depend on the legal challenge alone, however, Spandana leadership triaged the most pressing challenges and made some difficult business decisions.

Hard Solutions for A Long Recovery

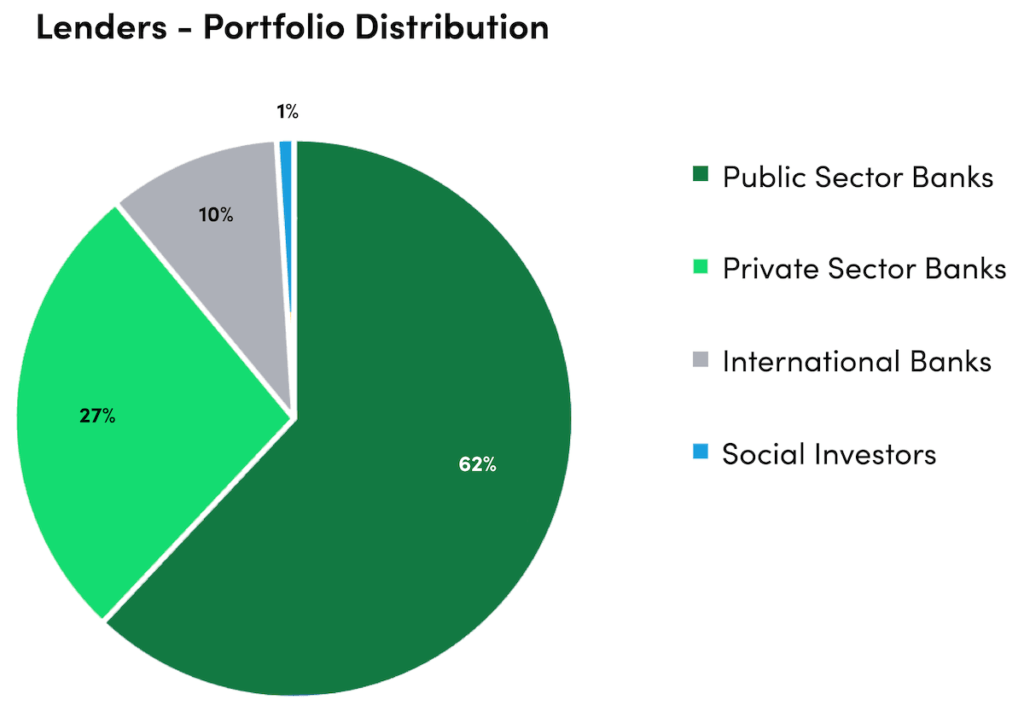

The senior management team quickly recognized that liquidity, crucial for ensuring the company could continue operations, was the top challenge. But for Spandana, additional liquidity in the form of financing was hard to come by as it had taken on debt from 48 lenders to fuel its growth.

The team ultimately felt that a corporate debt restructuring (CDR) would be appropriate to get needed liquidity and avoid default. ICICI Bank and SIDBI, Spandana’s largest lenders, agreed with the management team’s assessment that Spandana needed a CDR. The team needed to convince the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), however, because it did not allow such a facility for NBFCs. Spandana’s executive team, along with ICICI and SIDBI, began efforts to persuade the RBI to authorize debt of NBFCs as eligible for a CDR. At the same time, the management team held discussions with its investors to gather internal support for a CDR, pending RBI approval.

In 2011, after months of dialogue with the RBI, Spandana, along with other NBFCs in AP, finally got what they wanted: authorization to proceed with a CDR in accordance with guidelines established by the new policy. The RBI also established rules, which played an important role in stabilizing the regulatory environment on issues related to operational process, customer protection, and governance. It also created a separate class of institutions for NBFC-MFIs for regulatory purposes.

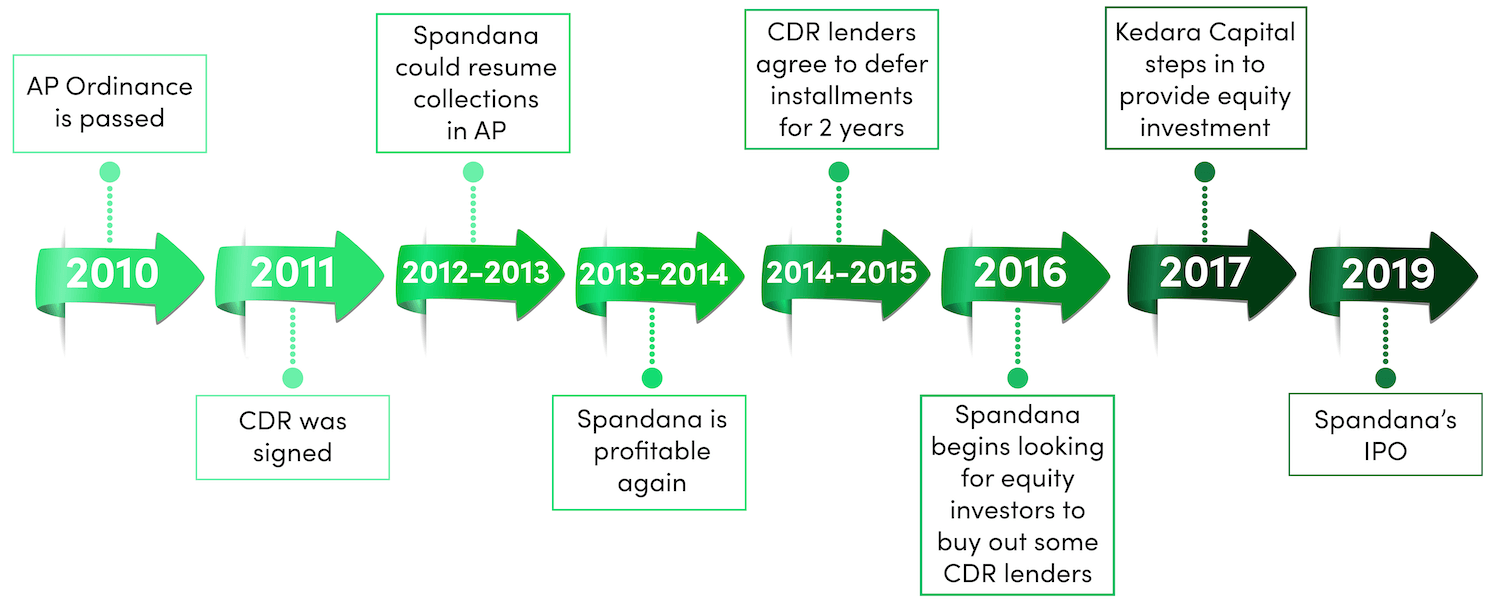

ICICI and SIDBI managed to persuade most lenders to sign on to the CDR package by emphasizing the increased chance of recovery over time with improved ground-level conditions, although some lenders did not agree to the CDR and were left out. In September 2011 (see timeline graphic below) Spandana’s investors signed the CDR, which would restructure their INR 21.46 billion in loans outstanding to address its exposure in AP and assist with liquidity challenges. The CDR had two components:

1. Optionally Convertible Note (OCN)

INR 10 billion (46 percent) of the outstanding loan value, an amount equivalent to AP portfolio that was deemed irrecoverable, was restructured into a convertible quasi-equity instrument. A redemption premium of 12 percent per annum was payable at redemption. The lenders also had the option to convert these instruments into equity shares of the company, an option Spandana hoped investors would exercise.

2. Term Loan

The remaining INR 11.5 billion (54 percent) was bundled into a 72-month term loan repayable in monthly installments at 12 percent interest from April 2012. The term loan was secured by a pledge of 7.27 million Spandana shares owned by its founder, Padmaja Reddy.

Leaner and Stronger Operations

While the CDR resolved the initial liquidity issues keeping Spandana from defaulting, many other business and operational challenges had to be dealt with in order to ensure long-term survival. The first, most immediate challenge was Spandana’s increasing operational costs coupled with declining revenue. After an exhaustive analysis of its operational costs, the team decided to reduce its number branches and staff.

The next challenge was to establish strong practices related to customer experience and engagement. This included organizing institution-wide staff trainings on appropriate field behavior and client communications. To further improve field behavior, the staff remuneration structure was changed so that 70 percent of staff salaries were fixed, as opposed to 30 percent before the crisis. The goal of this was to encourage staff focus on portfolio quality instead of growth.

Staff members were encouraged to focus on portfolio quality instead of growth.

In 2012, after waiting almost two years, the Supreme Court ruled that Spandana could restart lending and recovery operations in the state. This decision restored Spandana’s recovery efforts and it managed to collect INR 10 billion between FY 2011 and FY 2017. With collections resuming in AP, and the new liquidity provided by the CDR, Spandana decided to expand its portfolio to other states to counter perceived overexposure to AP. By deploying capital in other states, Spandana managed to lower its exposure in Andhra Pradesh to 3.1 percent of its active portfolio in 2017, significantly lower than the pre-crisis level of 51 percent.

Spandana also needed to show it was on track operationally. In FY 2014, Spandana reported disbursing INR 16.67 billion in new loans. The improved collection rate and business performance gave confidence to the CDR lenders, which helped Spandana persuade them to defer CDR payments for a period of two years, from January 2014 to December 2015. This agreement allowed Spandana to continue using the cash from collections to reinvest in the expansion of lending operations. ICICI Bank also stepped up to provide an INR 11.5 billion credit facility to boost portfolio growth outside AP. As a result of these efforts, Spandana was able to strengthen its financial performance and condition and begin servicing the CDR when initial payments came due in 2016.

Profitability and A Strong New Ally

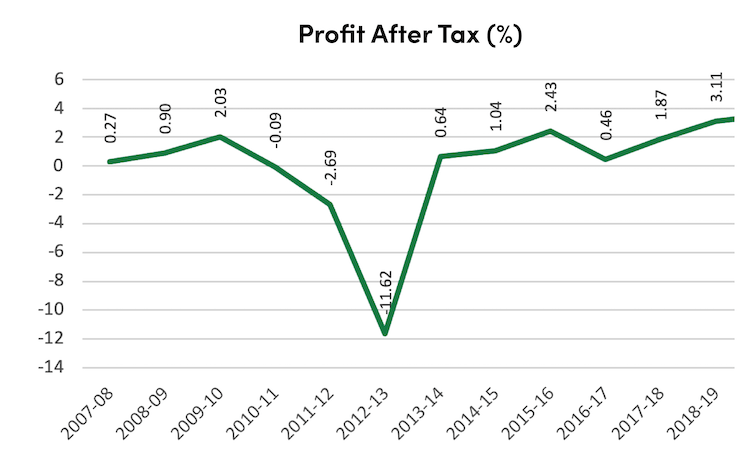

The shift in strategy, resumed collections in AP, and operational changes allowed Spandana to become profitable starting in FY 2014 (2013-14) after three years of losses (see graphs below). In FY 2016, Spandana reported a profit of INR 2.45 billion. Moreover, its capital adequacy ratio, which was negative the prior two years, turned positive in FY 2017.

Although Spandana attempted to fulfill the CDR obligations, there were times when collections and revenue were not adequate to cover payments. Therefore, in 2016, the management began scouting for investors to obtain new funding and buy out the CDR lenders who did not intend to convert their investment into equity. While Spandana continued to negotiate the payoff of the OCN, time was running out fast to find new equity investors. In 2017, Kedara Capital, recognizing Spandana’s long-term value, invested by buying out the remaining portion of the OCN. Spandana was also able to get a consortium of banks to provide a loan of INR 11 billion to pay off the outstanding term loan of the CDR. Following these moves, Spandana exited the CDR package, which assisted in improving its credit rating

By 2019, Kedara Capital gradually increased its investment in Spandana to 59.1 percent. As a majority shareholder, Kedara took an active role to help Spandana consolidate the number of lenders and increase the availability of capital at lower cost. With the support of Kedara, the number of lenders was reduced to five, and Spandana was able to obtain new financing for business expansion. Kedara also advised the company to improve its governance structure by bringing in industry experts to serve as independent directors. This rebuild fueled Spandana’s operating and profit margins while enabling the upgrade of its credit ratings.

Kedara advised Spandana to improve its governance structure by bringing in industry experts to serve as independent directors.

Finally, 10 years after the AP crisis, Spandana came full circle when it successfully launched its IPO in 2019. It went well: the company’s share price rose more than 33 percent between August 2019 and late February 2020. Then, COVID hit…

What are some of the dos and don’ts and key success factors that the microfinance sector can learn from the Spandana case? CFI’s forthcoming report, Weathering the Storm II, will draw on lessons from Spandana and cases from microfinance institutions in four other markets – Azerbaijan, Bosnia, Palestine and Nicaragua. See the original Weathering the Storm report from 2011 here.

The author is extremely grateful to N.K Maini, ex-Deputy Managing Director of SIDBI, Gourisankar Gollapudi, CEO of Manaveeya Development and Finance Limited, Nitin Agarwal (former CEO of Spandana between 2010 and 2014) Prakash Kumar, CGM, SIDBI, for agreeing to be interviewed about the Spandana crisis and revival. We would also like to thank Tanwi Kumari for her invaluable research assistance on this project. This case would not be complete without their contributions.