Topics

- Challenges and Crises

- Consumer Protection

- Credit

- Customer Centricity

- Digital Financial Services

- Enabling Environment

- Governance

- Microfinance

- Policy, Regulation and Government Initiatives

Series

Past crises have taught the microfinance sector a lot about weathering storms. Microfinance institutions (MFIs) are once again facing challenging times. This case study is part of a series that CFI, in partnership with the European Microfinance Platform (e-MFP) and the Mastercard Center for Inclusive Growth, is publishing to (re)visit tales of tough times and resiliency in five markets – Azerbaijan, Bosnia and Herzegovina, India, Nicaragua and Palestine – and discuss how MFIs, with the help of their investors and other stakeholders, emerged and thrived. The lessons learned from these cases will be compiled and examined in a forthcoming report, Weathering the Storm II, a follow up to the first edition published in the aftermath of the global financial crisis a decade ago. The hope is that these lessons will be applicable to not only the COVID-19 response, but to future crisis responses as well.

In the spring of 2018, Alaa Sisalem, the general manager of Vitas Palestine, was reviewing the materials prepared for an upcoming board meeting. In the first quarter of 2018, Vitas Palestine – part of Vitas Group, a holding company that operates non-bank financial services companies in the Middle East and Eastern Europe – achieved 95 percent of projected portfolio growth while maintaining a PAR 30 (loans in arrears for over 30 days) of 2.1 percent. As Sisalem looked through the growth projections for the year, he glanced outside his window at the bustling streets of Ramallah. He thought about Vitas Palestine’s clients and their ability to pay in the current economic conditions, and he realized that while the financials didn’t show it yet, a major storm was coming.

A few weeks earlier, in April 2018, the salaries for about 38,000 civil servants in the Gaza Strip were delayed. The following month, the Palestinian Authority (PA) cut staff salaries by 20 percent. This marked the beginning of a crisis for Vitas Palestine. The civil servant salaries were unpaid or delayed multiple times, especially in Gaza, which took a toll on the local economy. Gaza’s economy was already under severe stress because of movement restrictions brought about by the conflict between Hamas and Israel. Hamas gained control of Gaza in the 2006 elections, but the PA continued to administer payroll in the region, causing tensions between Hamas and the PA.

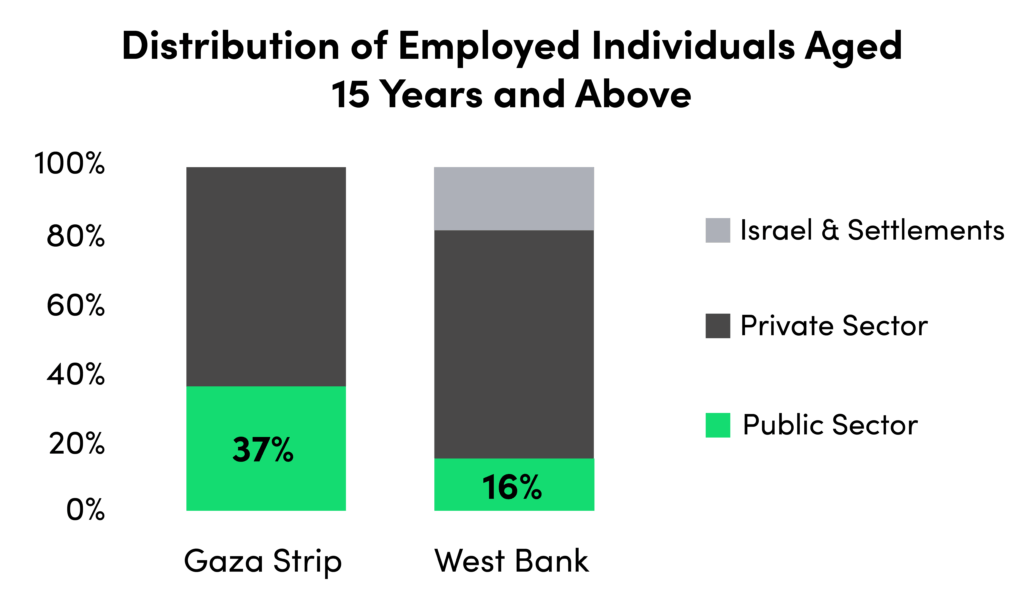

Civil servant salaries significantly impact the Palestinian economy because of the low rates of private investment and a low labor force participation rate of 44 percent. The territory has one of the highest unemployment rates in the world, with a quarter of the working-age population unemployed. The situation is even more dire in Gaza, which accounted for 29 percent of Vitas’ 2018 gross loan portfolio and has an unemployment rate close to 45 percent. In Gaza, 37 percent of the employed individuals worked in the public sector, and therefore, interruptions to civil servant salaries tend to have a cascading effect on consumer spending and the local economy.

The West Bank economy is more diversified than Gaza, with 16 percent of all employed individuals working in the public sector. Yet, there were concerns that the crisis would seep into the West Bank after the Israeli government passed a law in 2018 that allowed unilateral deductions from the tax revenues it transfers to the PA. The deductions are equivalent to the amount paid by the PA to families of Palestinians killed or put in jail due to the conflict with Israel (about $12 million per month). The tax revenues transferred from Israel represent more than 60 percent of PA’s total revenues, and the deductions would further strain PA’s budget.

The Board Moves to Head Off Crisis

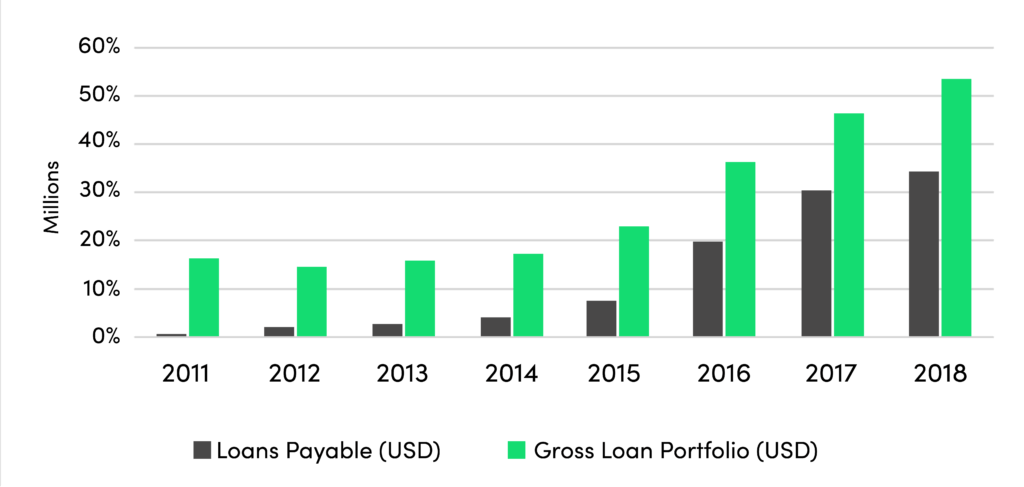

Vitas Palestine began in the early years of the microfinance sector as a USAID project. The incorporation of Vitas Palestine as a for-profit company in 2014 made it easier for the company to borrow from local and international lenders. This ease of access to funding contributed to the rapid growth of Vitas’ loan portfolio (see graph below).

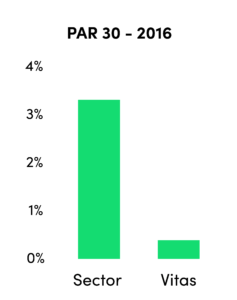

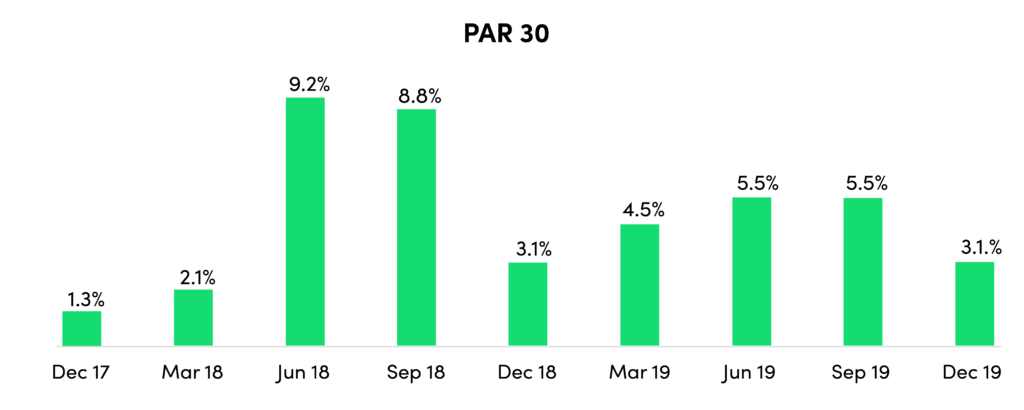

But when the Vitas Palestine’s board met in May 2018, the region’s worsening economic conditions dominated their discussion. Following the salary interruptions in early 2018, Vitas Palestine began to experience declining portfolio quality, with a 10 percent drop in the collection rate, resulting in a PAR 30 of 6 percent for the total portfolio in May, and a PAR 30 of 16 percent in Gaza. This was a significant increase from the December 2017 PAR 30 of 1.32 percent. Vitas Palestine had a strong debt to equity ratio of 1.81 at the end of 2017, but in 2018, the declining portfolio quality led to a breach of delinquency covenants.

The board and the management agreed that Vitas needed to prepare for further challenges due to the political instability. After deliberations with management, the Vitas board advised against aggressive growth targets and counseled the management to prioritize three areas: managing liquidity, improving portfolio quality, and controlling operational costs.

Managing liquidity, improving portfolio quality, and controlling operational costs were three priorities for the board.

Sisalem had been through numerous crises at the company, ever since CHF Ryada, Vitas Palestine’s predecessor, disbursed its first housing loan in 1995. As Sisalem was formulating the plan of action to tackle the salary crisis, he knew from experience that maintaining strong relationships with clients, investors, and staff would be crucial to Vitas’ survival. The management team at Vitas ensured open communication with its staff and investors. The management also recognized that the front-line staff plays an essential role in deepening client relationships and continued its investment in client relationship officer training to prepare staff to handle difficult conversations with clients.

In order to control operational costs, the management team performed a detailed analysis of its expenses and identified ways to optimize operations. Their analysis showed that there was sufficient liquidity to tackle the next six to nine months without exploring drastic measures to reduce costs. Further, the loan officers’ incentives were based in part on portfolio quality, and the increase in PAR 30 during the crisis led to lower incentives paid by the company. This variable component of the compensation structure led to lower staffing expenses and aided the management efforts to lower costs.

Alaa Sisalem, General Manager“At Vitas Palestine, we believe there is opportunity in every crisis. Our role is to remain on the ground continuing operations and to never stop lending. Our clients sometimes need bridge loans and working capital when the times get tough, and our openness and availability to our clients during crises has been key to our long-term success.”

Client (and Lender) Centricity

Prior to the crisis, Vitas Palestine had the lowest PAR 30 in the Palestinian microfinance sector, partly because of its attention to preventing client over-indebtedness. Vitas provided loans for housing, businesses, and consumption. For all the product offerings, the company’s credit analysis process ensured that the borrower had a margin to make a loan payment, even if their income or sales declined temporarily. After disruptive violence in the territory, loan officers and supervisors would contact each client, find out if they needed any additional support, and referred them to NGOs or other local programs, if required. The staff avoided asking about payments in the first call but assessed their situation during their conversations and segmented the clients based on the ability to pay. In some cases, Vitas would enter short-term informal arrangements that resolved loan delinquency without having to take their clients through the court system. Sisalem and his team relied on the same client-centric approach while dealing with non-payments during the salary crisis.

In addition to client centricity, Vitas had built strong relationships with its lenders over the years. Sisalem and his management team prioritized communicating early and often with the investors to keep them updated on the situation. Many of Vitas’ existing lenders had been with the company through many crises over the years, and the company’s proactive communication gave them the confidence to agree to waivers in the event of breaches of covenants. Vitas took a long-term view and continued to forge lender relationships during the crisis, anticipating the demand for loans once the economic conditions improved.

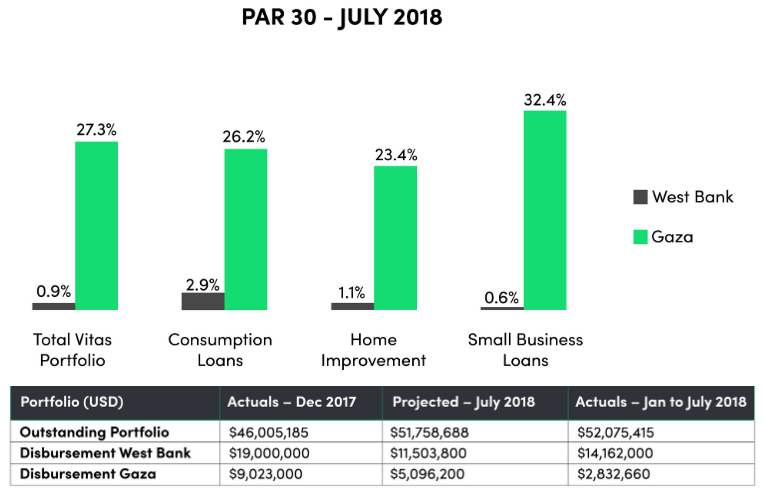

When the board met again in September 2018, they reviewed the measures implemented since the last meeting. As predicted, the portfolio quality had deteriorated, with PAR 30 at 9.3 percent in July. The PAR 30 for the portfolio in Gaza had risen to 27.3 percent (see graph below). There was a significant drop in loan disbursements in Gaza, but the higher demand in West Bank in 2018 had offset the lower disbursements in Gaza (see table below). After reviewing the results, the board asked the management to continue its focus on portfolio quality, especially in Gaza.

Digital Readiness

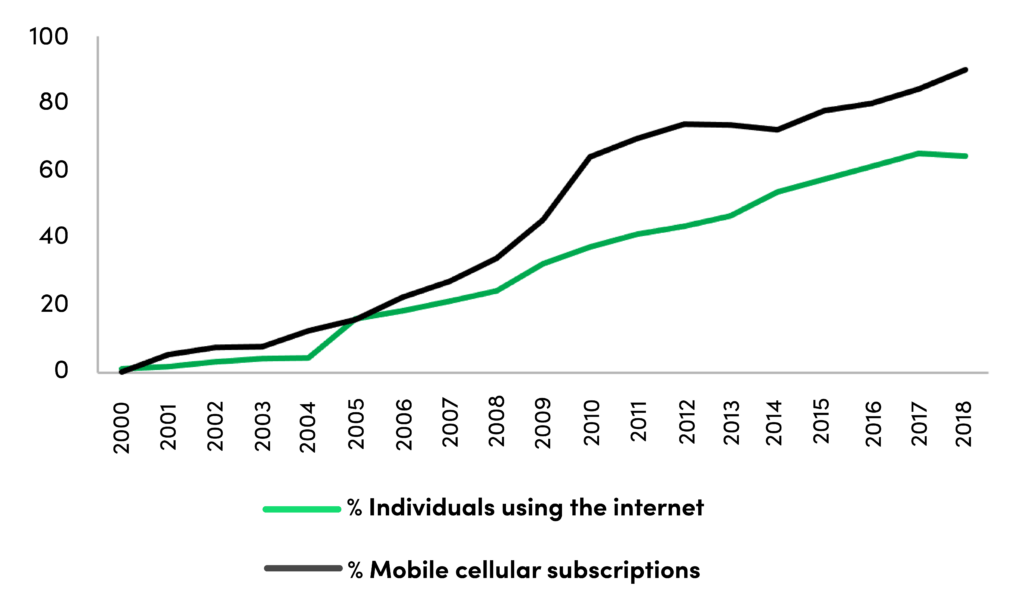

The board also recognized that the company needed to refocus its digital transformation efforts to effectively serve its clients after the crisis. The Vitas Group began digital transformation efforts in 2018, and as part of the network-wide initiative, Vitas Palestine underwent a digital transformation readiness exercise. The exercise highlighted the opportunity to improve the utilization of its assets and increase market share by leveraging data and technology. Vitas Palestine’s operations had traditionally been high touch, but consumer behavior was changing, and about 65 percent of Palestinians used the internet in 2018. The company had a strong social media presence, with over 250,000 followers on Facebook, but the data was being analyzed manually for lead generation. Sisalem and his team bought into the digital strategy vision and saw it as an opportunity to rejuvenate the growth of its portfolio. A report published in 2017 estimated the microfinance market in Palestine to have between 245,000 and 345,000 unserved clients with a potential market between $630 million and $900 million. The company’s digital readiness assessment, and subsequent strategic plan, would provide a path to reaching the underserved market while lowering cost.

Following the digital readiness assessment, the first set of initiatives aimed to modernize Vitas Palestine’s existing processes to increase efficiency and improve customer experience. The Vitas Group leveraged partnerships to reposition its technology architecture. The Vitas Group also planned to establish Vitas Lab to manage innovative digital projects at all its subsidiaries and encourage internal knowledge sharing. Vitas Palestine relied on these digital transformation efforts to emerge stronger after the crisis.

In March 2019, in order to take a stand against the deductions carried out by Israel, the PA refused to accept the transfer of tax revenues. The absence of the tax revenue caused severe strain on the economy until September 2019, when the PA started accepting the revenues again. During that period, the local banks in Palestine had to lend to the government, prompting Vitas Palestine to look at international lenders.

Sisalem and his team bought into the digital strategy vision and saw it as an opportunity to rejuvenate growth.

Vitas leveraged its long-standing history of working in the region to cultivate new relationships with international lenders. In 2019, Vitas Palestine faced a temporary decline in collections. Still, its early focus on portfolio quality and client relationships and a conservative approach to loan loss provisioning, helped the company maintain a strong position in the microfinance sector.

Vitas made numerous strides in its digitalization journey that allowed the company to improve operations in 2019. In April 2019, Vitas Palestine introduced simple digital loans through the Facebook interface for faster lending decisions and a better customer experience. Although it was not an end-to-end digital lending product, because Palestine does not allow electronic signatures, Vitas had taken a significant step towards integrating digital channels into its product offering. Vitas Group hired a chief digital officer to accelerate the implementation of its digital strategy in November 2019. Later in December 2019, Vitas Palestine introduced an app for clients to apply for loans, and track their loan status and payments. By the end of 2019, Vitas Palestine had completed the digital transformation road map by digitizing internal processes and offering digital products.

By the end of 2018, Vitas managed to improve the PAR 30 to 3.1 percent (9.5 percent in Gaza), with 9.3 percent rescheduled and 0.71 percent of the portfolio written off (see graph below). The improvement in portfolio quality was encouraging, but Sisalem and his management team remained wary of the possibility of the economic crisis seeping into the West Bank following the deductions in tax revenues transferred from Israel to the PA. The loan portfolio growth slowed down in 2018 and 2019, while Vitas invested in building strong internal structures.

By the end of 2019, Vitas Palestine had completed the digital transformation road map by digitizing internal processes and offering digital products.

The company’s outstanding loan portfolio shrunk slightly in 2019 to $51.8 million from the $53.5 million at the end of 2018 due to the economic crisis. Even though the outstanding portfolio shrunk in 2019, the number of active clients grew by 6 percent due to the shift of the disbursement strategy towards micro businesses. With its continued efforts to manage delinquency, Vitas Palestine ended 2019 with a strong PAR 30 of 3.1 percent.

In 2020, Palestine’s economic crisis was far from over, but Vitas Palestine has managed to take control of its portfolio and has built a robust digital infrastructure. Vitas Palestine’s resiliency, digital strategy, and improved portfolio quality have allowed the company to secure new lending relationships with development financial institutions, FMO and Proparco. Sisalem and Vitas remain committed to serving their clients in Palestine, even when the future remains uncertain.

What are some of the dos and don’ts and key success factors that the microfinance sector can learn from the Vitas case? CFI’s forthcoming report, Weathering the Storm II, will draw on lessons from Vitas and cases from microfinance institutions in four other markets – Azerbaijan, Bosnia, India and Nicaragua. See the original Weathering the Storm report from 2011 here.